Introducing ‘Our Future Coast’ at Sunderland Point

The Point End: Photo Dom Green

For our first article in 2026, Joseph Earl has kindly agreed to write about the early stages of the ‘Our Future Coast project taking place in the village involving the full community.

At a time of increasing flood and erosion risks from climate change, and when traditional coastal protection options like concrete sea walls and rock armour are becoming increasingly unaffordable and unsustainable for many coastal areas around the UK, there is a pressing need to explore alternative options to manage coastal change.

The Sunderland Point community have been involved in a project since April 2025 to test and trial alternative options like ‘Nature Based Solutions’, which aim to work with natural processes to manage local coastal challenges. The project is one of 17 case study sites around the North West coast included in the Our Future Coast programme, a DEFRA-funded initiative which aims to enhance the resilience of coastal communities to flooding and erosion using Nature Based Solutions like saltmarshes and sand dunes.

Sunderland Point residents Moira Winters and Jo Powell were instrumental in getting the project discussed and approved on behalf of the village, and ultimately setting the direction of the project. Crucially, the project seeks to offer the local community a voice in coastal management decisions that affect them, something 83% Sunderland Point residents do not feel they currently have [1].

To support community involvement and help progress the project, residents are working with Morecambe Bay Partnership, who are also involved in six other Our Future Coast sites in Lancashire and Cumbria. Ultimately, the project at Sunderland Point places people at the heart of Our Future Coast by designing Nature Based Solutions with the community.

Working Together

At the start of the project, all Sunderland Point residents were invited to join a project Task Group. The Group, which has met six times to date, aims to promote partnership, discussion, and collaboration amongst the community and key stakeholders involved in developing Nature Based Solutions. One of the Group’s first tasks involved setting a project vision, which states –

By March 2027, we want Sunderland Point to be a place where we:

Understand how the estuary and saltmarsh are changing

Know where and how we can intervene with Nature Based Solutions

Have tested different Nature Based Solutions and have learnt something about their effectiveness for managing flooding and erosion

Better understand our future flood and erosion risks, and have explored different options for managing or adapting to them in the future

Have built a legacy whereby we know what the next steps are, have a plan for the future, and know how to secure funding.

[1] Statistic from a survey of Sunderland Point residents in May 2025.

Understanding how the estuary and saltmarsh are changing

Building a better understanding of past and present changes in the coastal environment is an important first step to inform what Nature Based Solutions could be suitable for Sunderland Point, and where they might work best. To achieve this, the Task Group got involved in and set research questions for three overlapping studies, each exploring how the estuary and saltmarsh environments are changing.

To research how the coastline has evolved historically over the past two centuries, Claire Bradshaw, Morecambe Bay Partnership’s Archaeology & Heritage Officer, undertook archive visits with residents and examined 100’s of documents, paintings and photographs.

To shed light on more recent changes in the coastal environment post 2000, Charlotte Evans, an intern at Lancaster University, collected and analysed a variety of primary and secondary coastal data, including hydrodynamic data, satellite imagery, topographic profiles and LiDAR scans (a remote sensing technique for monitoring elevation). Charlotte’s fieldwork also involved the use of ‘Mini Buoys’ - low-cost tools to monitor various changes in the intertidal zone – which were built and deployed by residents (Picture).

Figure 1. Deploying the Mini Buoys (Credit: Charlotte Evans)

Lastly, Dr Liz Edwards used 'clip:bit' software with children from Overton Primary School and residents to survey and map the extent and types of saltmarsh plants found along Sunderland Point’s Eastern Shore. Together, these three studies have helped to provide a clearer picture for how the distinct areas of coastline at Lades Marsh, West Shore and East Shore have changed over time (Picture).

The three coastal areas studies in Claire’s and Charlotte’s analysis of past and present coastal change (Credit: Google maps)

For Lades Marsh, historic maps indicated that the saltmarsh has been increasing in extent since at least mid-1800, an increase that was possibly accelerated by the building of the Lune training wall in 1847-1851. However, LiDAR data collected between 2006 and 2023 suggests the marsh edge is now eroding, although the main area of saltmarsh is typically growing in height. Similarly, for West Shore, the saltmarsh has increased in the extent and height since at least 1913, particularly in the north of the marsh, with LiDAR data confirming this trend has continued up to 2023.

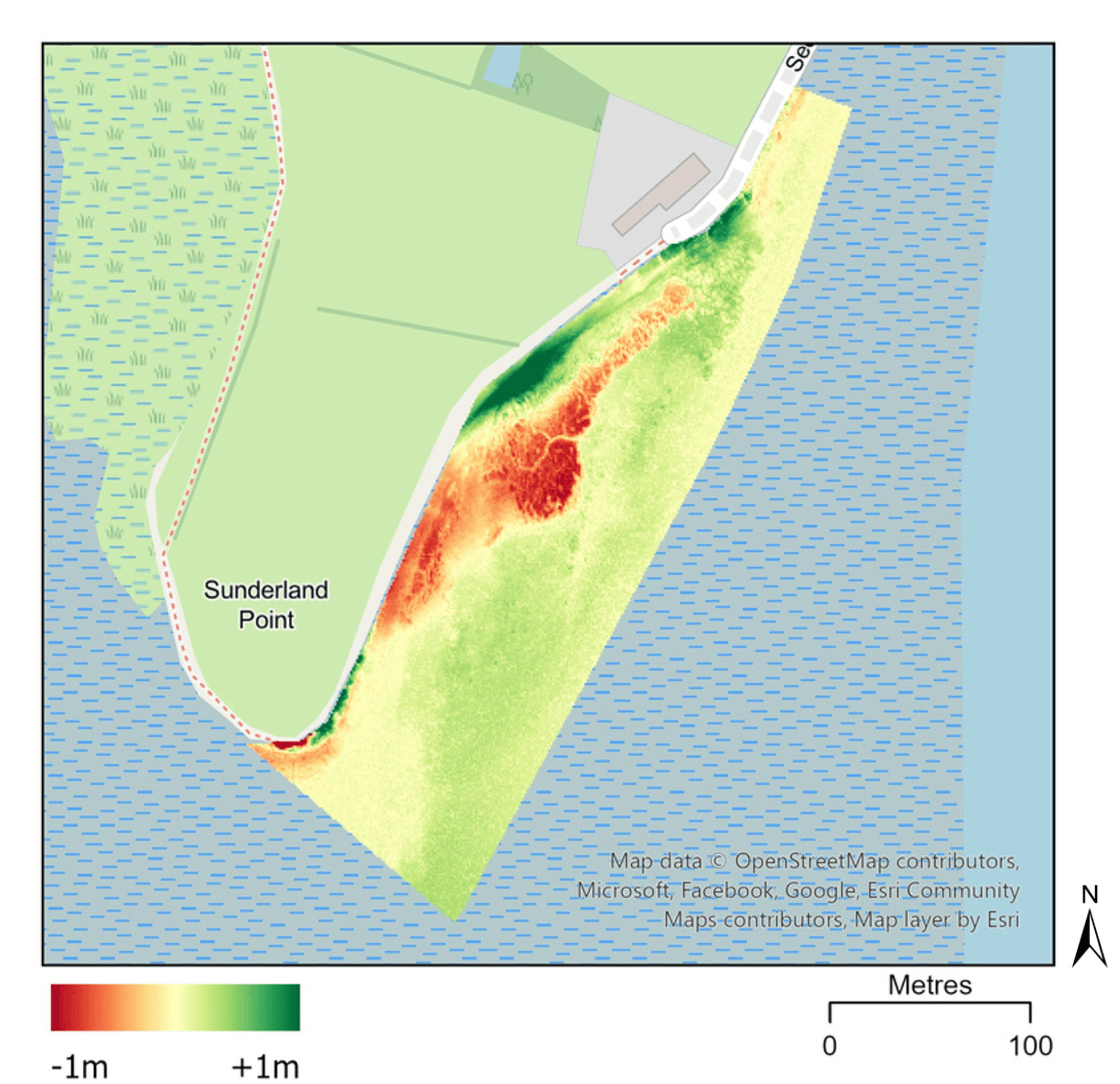

For East Shore, which spans from the end of the causeway to Point End, there is limited historical evidence for the presence of saltmarsh. But, photographs and aerial imagery from the mid-to-late 20th century do show that areas of saltmarsh were present, including in the embayments between Old Hall and Point End, and between First and Second Terrace. Saltmarsh is still seen in these areas to date, although they have contrasting fates; saltmarsh plants have thrived between the Terraces, whilst significant erosion has been observed between Old Hall and Point End (Pictures).

Figure 2. The extent of elevation loss (red area), and hence saltmarsh erosion, between 2006 and 2023 along the coastline from Old Hall to Point End is clear in the LiDAR data (Credit: Evans, 2025).

Figure 3. Saltmarsh between First and Second Terrace has increased in both extent and elevation between 2006 and 2023, as indicated by the dark green shading in this LiDAR plot (Credit: Evans, 2025).

Figure 4. Saltmarsh between First and Second Terrace.

Reasons for the differences in erosion or accretion rates between these two areas of saltmarsh is uncertain, although Charlotte’s analysis of the Mini Buoy data between Old Hall and Point End did suggest that there are now favourable ‘windows of opportunity’ (time periods without disturbances, such as tidal inundation and/or hydrodynamic forcing) for saltmarsh plants to establish in this area. Moreover, Liz’s saltmarsh surveys in this vicinity highlighted an abundance of pioneer saltmarsh plant species like spartina and samphire - the vegetation that colonises intertidal mudflats in the early stages of saltmarsh development – which help to support Charlotte’s conclusions and suggest restoration of this marsh may be feasible[1].

Know where and how we can intervene with Nature Based Solutions

The conclusions from these studies provided the Task Group with the ability to make informed decisions about the most feasible locations to test Nature Based Solutions for saltmarsh restoration. Lades Marsh and West Shore were quickly ruled out from any solutions, both because of their inaccessibility for physical on-the-ground works and, as is the case for the saltmarsh along West Shore, its continued increase in extent and elevation limits the need for ‘restoration’.

Comparatively, East Shore proved opportune for Nature Based Solutions. As well as offering easy access and opportunities for saltmarsh restoration or expansion, East Shore also hosts Sunderland Point Village, therefore any solution here may provide the greatest benefit to the community.

Having established where Nature Based Solutions may be most feasible, the Task Group’s attention turned to what solutions could be tested and trialled along East Shore. The Task Group were introduced to a suite of Nature Based Solutions from the UK and beyond that have been used to protect eroding coastlines, create ‘temperate mangroves’ and restore saltmarshes.

For saltmarsh restoration, solutions included options to nurture marshes to expand by harvesting, growing and planting saltmarsh, or by placing biodegradable structures into the environment that can trap sediment and encourage plant growth. More physical interventions were also presented to the Task Group, for instance polders and brushwood groynes, which seek to create favourable conditions for saltmarsh restoration over large scales.

[1] You can read Charlotte Evans’ full report here: Sunderland Point Baseline Coastal Processes Report.pdf

Nature Based Solutions for saltmarsh restoration: Biodegradable ‘BESE’ elements deployed in Morecambe Bay (Left) and a polder in the Netherlands (Right) (Credits: Ellie Brown & Joseph Earl)

Together, the Task Group discussed and agreed upon four different Nature Based Solutions to test in different areas along the East Shore (Picture). These solutions will be presented as proposals to statutory agencies and the wider Sunderland Point community in early 2026, with the ambition to deliver the first tests and trials in the summer. The Group have many potential barriers and obstacles to overcome before then, but by working together, we hope to make a success of the project and deliver the vision of Our Future Coast.

References

Evans, C. (2025) Sunderland Point Baseline Coastal Processes Report. Available at: Sunderland Point Baseline Coastal Processes Report.pdf

Joseph Earl, December 2025

Note on the Author

Joseph works part time for Morecambe Bay Partnership as Co-lead for Engagement on the Our Future Coast project. He has a keen interest in working with communities in coastal management, having completed a PhD on the subject in 2025.