Sunderland Point fishermen c1935, from left Hubert Townley, William Townley, Tom Gardner, Arnold Townley and Tom Spencer: Courtesy Rosemary Lawn.

Fishing

An introduction to fishing at Sunderland Point

This is an overview as the detail is almost endless. We hope this gives an appreciation of the methods and importance of fishing at Sunderland Point. Comments and suggested additions will be gratefully received.

From earliest habitation there will have been villagers whose livelihood was fishing. In the census records between 1841 to 1921 the main occupation was - by far - fishing. The family names stretch across the last two centuries, the Penningtons , Curwens and Dickinsons in the 19th century and spilling into the 20th century the two Gardner families, the Townleys, Bagots and Smiths.

Not so today, no longer is there any professional fishing at the Point.

The main species of the fishing seasons, Salmon, Shrimps, and Mussels have all but disappeared, as has the market for Whitebait and flatfish. Sea Bass is caught and sold but in small and infrequent quantities.

Images of fishing folk

Before we dive into summaries of fishing methods here is a selection of photographs of fisher folk. These are some our favourites.

Credit for photos: The collections of Wilton Atkinson, Hugh Cunliffe, Gilchrist family, Gardner family, Alan Smith, Lancashire Archives and Lancaster City Museums.

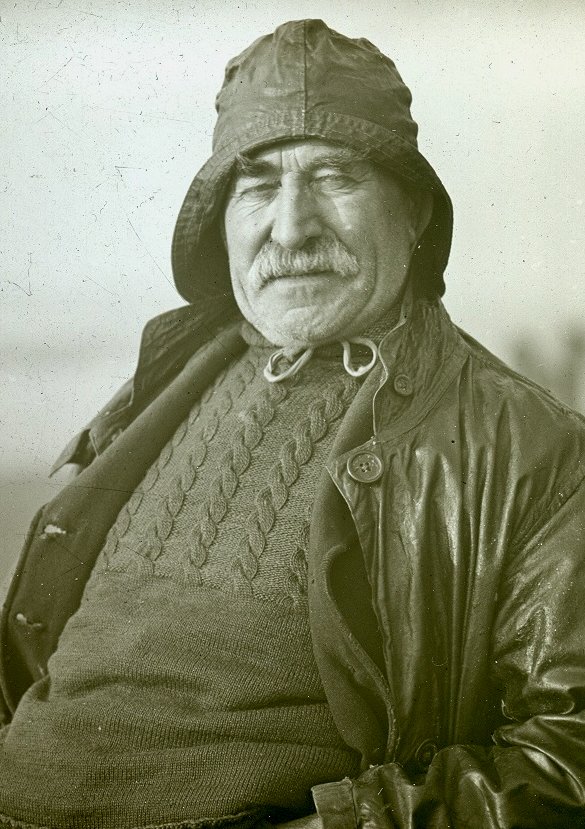

William ‘Barney’ Dickinson

William Townley (Snr.)

Richard W B Gardner

Thomas Jackson

Arthur Townley

Tom Smith and William Townley (Jnr.)

James ‘Shirley’ Gardner

James Gardner, Tom Spencer, and William Townley (Jnr.)

Richard Bagot

Gerrard Bagot

James W Gardner

Tom Gardner (Snr)

Arnold Townley, Tom Gardner (Jnr.) Hubert Townley.

Harold Gardner

Bert Smith

Prince and Philip Smith

Tom Smith

Peter Butler

Salmon - the king of fish

Adult Lune Salmon: Photo Alan Smith

The Lune is classed as one of the 48 major salmon rivers in England and Wales by the Environment Agency. In almost all those rivers the decline in fish numbers has been dramatic. Indeed, Salmon is an endangered species in most rivers flowing into the North Atlantic. In the 1960s the total catch in the Lune summer season would number thousands, but by the 2010s it was down to a few hundred. The current egg deposition rates in the upstream tributaries fall well short of sustainability. Today it is illegal, and will be for many years, to catch and kill Salmon from the river.

(For much more information see the article where have all the salmon gone

Perhaps 75% of fish - in the estuary - was caught by drift netting (Whammelling) with Haaf netting taking most of the rest. The licensed fishers were almost entirely based at Sunderland Point, Overton, and Glasson Dock.

Summary of salmon fishing methods

Baulks – fixed nets

Made illegal towards the end of the nineteenth century it is perhaps the oldest form of netting or more precisely trapping and was used by the monks of Cockersand Abbey.

A fixed line of stakes woven with willow branches sufficient to allow the river water to pass through reaches into the river and directs the fish to a gated pool. As can be seen in the photo the two men have hand-nets to extract the large fish, young salmon and other species would be set free by opening the gate. (The man standing is not wearing a kilt - it is the boys tartan jacket!)

A baulk (possibly Plover Scar): From the collection of Harold Gardner: Courtesy Rosemary Lawn.

Whammelling - a form of drift netting.

The word whammelling is thought to be of Norse origin. For the last century this method has been subject to increasingly strict regulation including the number of licences, the length of the net, the duration of the summer season and the hours in the week worked.

Whammelling was practised towards the end of the ebbing tide until just after the rise of the new tide. A length of net (up to 320 yards) would be released into the river and allowed to drift down with the tide hoping to catch Salmon (or Sea Trout) on their way to the upper reaches of the Lune to breed.

Tom Smith Whammelling – a fish is in the net, c1980: Photo Alan Smith

Prior to artificial fibres, nets would be made by menfolk of fishing families at home. The mesh would be knitted during the winter months and then fixed to an upper cord with floats (corks) and to a bottom cord fixed with lead weights at regular intervals.

James W. Gardner is measuring distance along the top cord to equalise to the distance between floats (corks): Photo c 1935 courtesy Lancashire County Council

Up to the 1960s nets made of natural fibres would be taken at weekends from the boats, hung on the posts to dry, cleaned of debris and repaired as necessary.

Fixing the net to the top and bottom cords (known as ‘stealing on’): Photo c1935 courtesy Lancashire County Council

Bert Smith (left) and his whammelling partner, Gerard Bagot, cleaning and repairing nets c1950s: From the collection of Alan Smith

The craft of Whammelling

A highly skilful ability demanding an intimate knowledge of the river - its ever-shifting currents, sandbanks, and bars - the habits of the salmon, the types and mesh size of nets, the timing of the tide (when it was low water), the weather and - the tactics of other fishermen.

In times past Whammel fishing was oar and sail powered, almost always with two in the boat, one rowing while the other ‘shot’ the net or hauled back to the boat. Managing the boat in all weathers, in the dark, required great stamina as well as skill and experience.

Keeping a net, in place, across the river, bank-to-bank was an art. The push and pull of the river often resulted in the net end to end, up and down the river, drifting uselessly in the middle of the stream.

Once out of position, the net is hauled in and re-shot. As the net drifts, salmon strike and get trapped in the net usually fighting vigorously to get free'; sometimes, barely caught in the mesh. Gently, the net is drawn back into the boat, coming to a section of net having a trapped fish. A hand net (known as a kep net) is positioned under the fish to ensure capture, pulled into the boat, and quickly killed.

The fish is despatched using a wooden truncheon known as a ‘priest’ (‘…issuing the last rites’)

Prior to 1999 there were 12 whammel licences and although the fisher-folk were in cooperatives and had their own representative society, competition, stoked by a pride in fishing ability, could be fierce.

Legal netting was allowed to start at Batehaven buoy and boats could and did drift down to the outer limit of the estuary. Boats would queue to begin in sequence of arrival. By the time the boat arrived at the lighthouse the next boat was free to go. This gap between boats to be largely maintained throughout the duration of the tide. So, timing arrival at Batehaven was vital. The river slides down into the estuary in a series of steps, bars, on the seaward side of the bar fish can wait, a period of rest before pushing upstream. Dropping onto and over a bar at the right time could have successful results.

The last – the ‘low water shot’ – as the tide slows to a stop was often the most important and to be in the right place was vital, as when the tide begin to rise it’s the signal for fish to move and the greater chance of capture.

With the tide properly rising, the boats return to home moorings - strict secrecy being maintained on caught quantities.

Haaf netting

The word is of Norse origin and the least changed method of Salmon fishing. A net is attached to a wooden beam. The Haaf netter stands in the river watching for fish swimming into the net. The Haaf beam is sharply lifted trapping the fish in the ‘purse’ of the net dispatched by use of the ‘priest’.

Fisherman with Haaf net c1890: From the collection of Wilton Atkinson

Haaf nets virtually unchanged in 2023: Photo Tessa Bunney

James Walker Haafing, summer 2023: Photo Tessa Bunney

A fish has ‘struck’ the net: Photo Tessa Bunney

A good sized Salmon, to be returned alive to the river: Photo Tessa Bunney

Draw netting (rarely practiced in modern times).

Using a small-meshed net, one end was fixed to the bank of the river held in place by one person. The remainder of the net was cast from a rowing boat with two persons, one rowing, one casting the net which went out into the current in the middle of the river. The net would begin to drift downstream. The boat, continuing to cast the net, would make its way back to the river side.

The action of the flowing river would make a ‘purse’ in the net. The three fishers ‘drew’ the net onto the bankside hoping it had trapped any fish passing past.

Shrimps

Brown Shrimps: Photo Tessa Bunney

Morecambe Bay Shrimps caught by James Walker, boiled and ready for shelling: Photo Tessa Bunney

At one time, not so long ago ‘Morecambe Bay Shrimps’ were as well-known and place linked as Lancashire Cheese, Worcestershire Sauce or Cumberland Sausage, and Baxter’s Morecambe Bay shrimps famously held the Royal Assent. Not so popular today. Shrimp numbers have declined, and the few caught and processed are regarded as a rare speciality. They have been almost completely overshadowed by the abundant supermarket prawn.

Shrimping would be an autumn/winter season occupation, beginning some weeks after the end of the Salmon season (31st August).

There were three main methods.

By hand – the simplest of all, think of a heavier duty butterfly net, but fixed to a triangular frame. Wading in shallow water on the sandbank the fisher would push the frame on the seabed hoping the Shrimps scurrying about on the surface would get trapped.

The catch would be bagged and eventually the contents riddled, discarding the small shrimps and unwanted species such as Crabs. The biggest Shrimps would be taken home ready for quick boiling and picking (removing the shell)

By horse/tractor – similar to the by hand method but by horse (or tractor) pulling a larger frame – trawl net – behind.

Prince and Tom Smith shrimping on Middleton Sands. To see this method follow this link to the article on the website which will also lead to the video. https://www.sunderlandpoint.net/blog/2-2

Shrimping using tractors: Courtesy the North Western Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority

Both methods resulted in larger catches, but the riddling, boiling, and shelling remained the same.

By boat – up to the full introduction of engine powered boats, shrimping was performed by sail boats. From Sunderland Point, boats would leave moorings and navigate out into the estuary and into the shallower waters of the bay off Heysham and Morecambe.

A trawl net would be released, consisting of a wide beam supporting a long net which would be dragged over the surface of the sea bed. Periodically the trawl would be hauled aboard, and the catch sorted through and riddled.

Moss Rose, Tom Smith’s Shrimp boat: From the collection of Dorothy Calverley

A Shrimp trawl under repair c1900, the beam has been made from two tree branches, probably washed ashore, and lashed together. The trawl irons at either end would have been made by the blacksmith in Overton: Photo courtesy Lancaster City Museums.

It’s Gravel cottage (Gravelly - number 2) in the background.

James Walker launching a Shrimp trawl 2023, here a scaffolding pole has been used for the beam: Photo Tessa Bunney

James riddling Shrimps to remove the juveniles: Photo Tessa Bunney

Often, the boat would have on board a wood fired boiler which would be lit and a large basin full of sea water heated to boiling. In batches the selected Shrimps would be quickly boiled – enough to change colour from a translucent brown into pink. The taste of a fresh caught Shrimp boiled in sea water, still hot, is divine.

Caught, riddled, and sorted Shrimps boiled on the boat: courtesy Morecambe Bay Trawlers.

Left to cool the shrimps would be returned home for shelling

Shelling (Picking) Shrimps

Picking Shrimps: Courtesy Furness Fish

Removing the shells from Shrimps is done by hand and although a relatively simple process, achieving the high speed necessary for commercial processing into the famous ‘potted Shrimps’ is a skilled operation.

A good Shrimp ‘picker’ could achieve an imperial pound weight in an hour, an expert with good sized Shrimps could exceed a pound and a half. A generation ago, the measurement of shrimps was in gills, pints, and quarts.

The Shrimp is held tail in left hand, head in right. The end of the tail is gently squeezed releasing the body inside the shell, a gentle pull releases the tail shell leaving the body exposed from the head. The body meat is removed from the head shell. The shell (scods) is waste.

Morecambe Bay Shrimps: Courtesy Furness fish

Whitebait

A small silvery fish, the young of Herring, Whitebait have been - and still are - plentiful in the river, but it wasn’t until the arrival of a fashionable desire for fried Whitebait beginning in London restaurants that made catching commercially sensible.

Whitebait dusted in flour quick fried and eat whole, head included: Courtesy Bellamy’s restaurant Covent Garden

From the late 1960’s until recently the fishing families set Whitebait nets on the shore. After high tide, the open nets would catch quantities of whitebait along with larger fish such as Sprats, and debris in the river. At low tide the end of the net would be emptied, and the tiny fish quickly taken for sorting, cleaning, and freezing.

In the last 10 years demand has fallen and the market all but disappeared. The last catches at the Point were in 2020.

The tied end of a Whitebait net

Caught whitebait and sprats in a riddle

Tessa's great bucket photo

Mussels

Mussels on mussel mud in Morecambe Bay

Once common all-around Morecambe Bay and commercially harvested and - despite a reappearance of a small mussel bank - mussel gathering disappeared a generation ago.

A map dated to 1900 showing mussel skears in Morecambe Bay

Gathering mussels at Sunderland Point. A William Wells painting.

In the left corner is a long handled ‘mussel craam’ used to rake mussels from the beds on the shore photo c1890: Courtesy Lancashire City Museums.

Fisherfolk would travel to the skears and sandbanks off Heysham and Morecambe as they were easier to gather than from the stony skears around the Point.

Mussels would be sent by wagon to Lytham St Annes to the water purification tanks before sale in the public markets. Others would be taken in 1 cwt sacks to Glasson Dock for rail transport to the East coast where they would be used as bait for the long line fishermen (usually for inshore cod). Womenfolk who were employed to open the mussels would complain if there were too many barnacles, as these would not just cut the fingers when handling but slow the rate of opening.

As demand decreased, mussels would be laid down in temporary beds further down the shore. Poles would be fixed among them with tin cans attached to frighten away the Oystercatchers who would pinch them. When new orders came through, they would be gathered and dispatched. Mussel gathering finally ended in the mid 1960s

During winter, mainly in the post war years up to the 1960s, another source of income for a few of the fishermen would be flatfish - Flukes - which could be trapped in set nets on the West Shore. Lower value Whiting and Eels caught in Whitebait nets were also marketed.

Present Day. Simon Ward returning from fishing for Sea Bass: Photo Alan Smith

Simon’s Sea Bass net in the river: Photo courtesy Yvonne Ward

Fishing Memorabilia

From the collection of Alan Smith

A collection of items including a 'tiernal' a locally hand made basket for collecting Flukes.

Corks (floats) from the top cord of a Whammel net.

A selection of knitting needles for making repairing nets

Kewls (word suspected Norse origin). Made probably from mahogany and used for checking mesh size when knitting net for Whammelling.

A Net barrow, used for carrying net at low tide from the boat to the top of the shore.

Haaf net license 1962. Issued by the Lancashire River Board.

Whammel net license from 1950 issued by the Lancashire fisheries board

A Mussel Craam for raking up Mussels on the shore

Mussel forks for hand picking (or piking) without handles and brand new. Made by George Jackson the Blacksmith in Overton.

Finally

There is no commercial fishing in the estuary. There are enthusiasts who put nets into the river and report fish such as Mullet, Whitebait and flatfish are in abundance but of little demand, there is Sea Bass but not in any quantity or predictability. Close relationships exist with the Environment Agency supporting the recovery of Salmon in the hope that one day sustainable fishing may return.

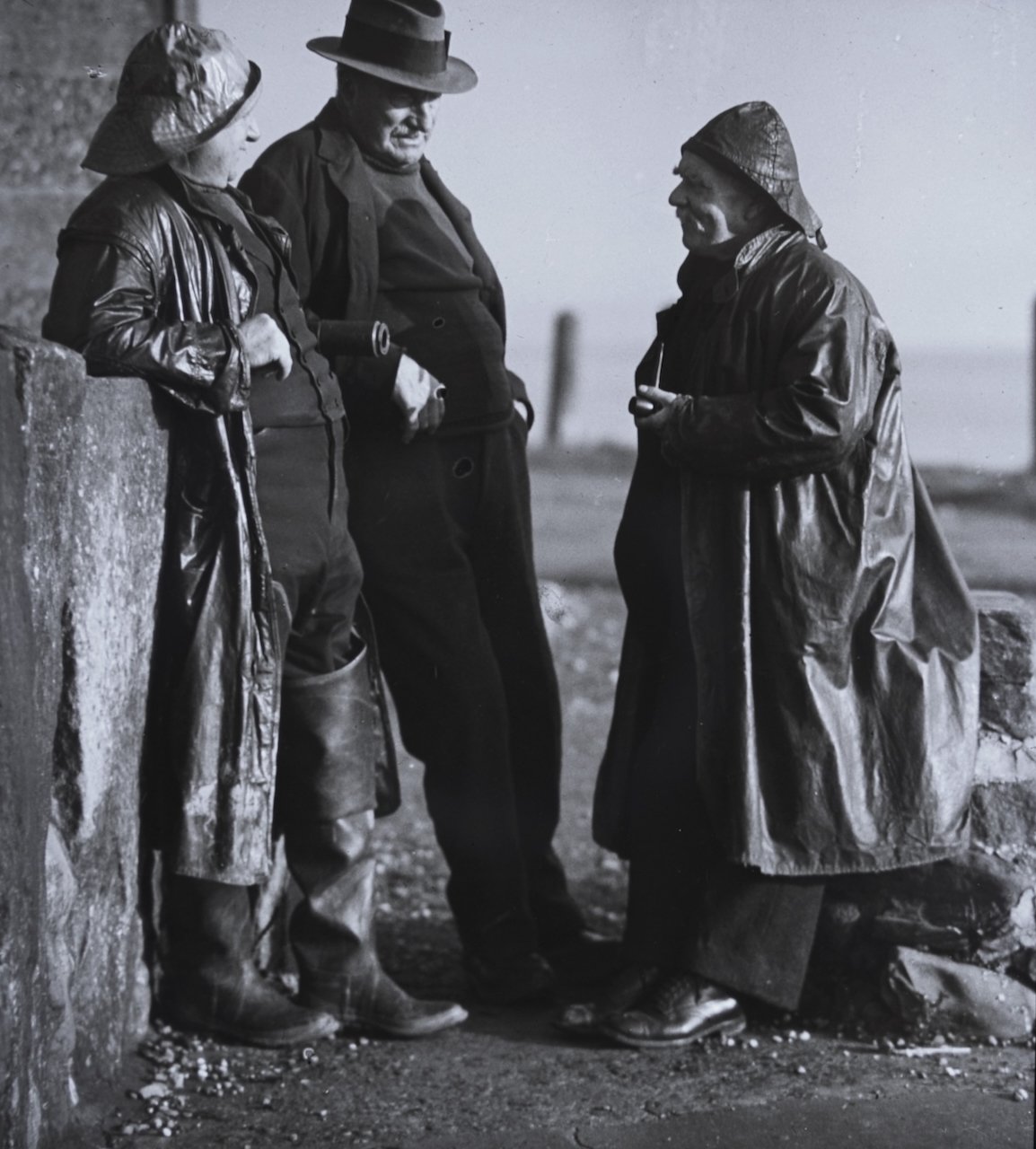

Tom Gardner and William Townley c1935: Courtesy Lancashire Archives