Where have all the salmon gone?

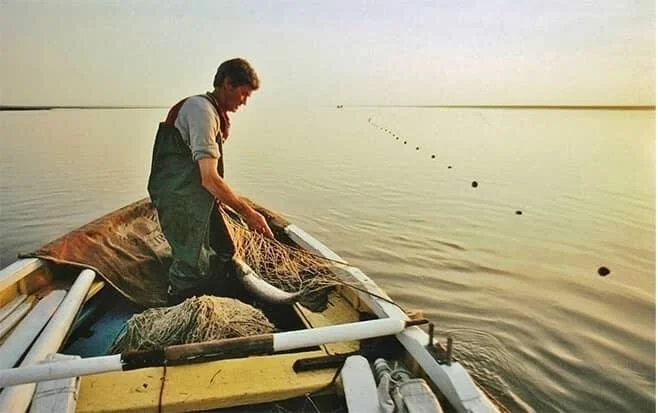

Lune salmon in times of plenty: Photo Alan Smith

Times change, well that might be true but not at Sunderland Point, it’s just the tide that comes and goes.

But there has been a deep and fundamental change over the last 20 years. Fishing as a professional livelihood has come to an end. Gone are the mussels, shrimps and the markets for whitebait and flatfish. The fishing families, once the backbone and fabric of village life, have all but disappeared.

But more than all of that, the salmon, the king of fish, has just about vanished. The decline in numbers is so severe that taking from the river is now forbidden and the level of spawning from returning fish is inadequate to re-establish its population.

It’s the law.

In December 2018, national bylaws were introduced to prevent the killing of salmon by nets in the Lune (and the main salmon rivers of England and Wales). The bylaw will stand for 10 years, and whilst reviews are permitted, it seems certain the ban will remain and even be extended.

The same now applies to rod fishing, from June 2021, and for a period of 10 years, by-laws require the mandatory release of all salmon caught.

It is indeed a bleak picture.

Detail from ‘A Lancashire Village’ by William Wells, 1909. Courtesy Edinburgh Museums. The iconic image of Salmon nets drying on poles with whammel fishing boats returning up the river.

Brothers Arnold (left) holding the salmon and Hubert Townley (right) with nephew Tom Gardner centre, 1950s. They are all descendants of salmon fishing families living on the Point that can be traced back to the early 1800s: From the collection of Harold Gardner.

To investigate what has happened we sent a crack team of detectives to write a letter to the Environment Agency.

The Environment Agency

The Agency is a public body sponsored by DEFRA (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs), who have within their responsibilities, the monitoring and protection of salmon. Over a period of weeks, a number of detailed documents were received. A sift through provides the essentials.

The 2020 River Lune Net Limitation Order and Byelaw Review provides the summary position.

‘Catches (by net) of salmon (in the Lune) have declined markedly through the June to August netting season over the last 20 years. There have been no changes to the allowable net fishing season, nor major changes in the fishing effort utilised. This decline primarily reflects a genuine decline in the abundance of returning adult salmon through those months.’

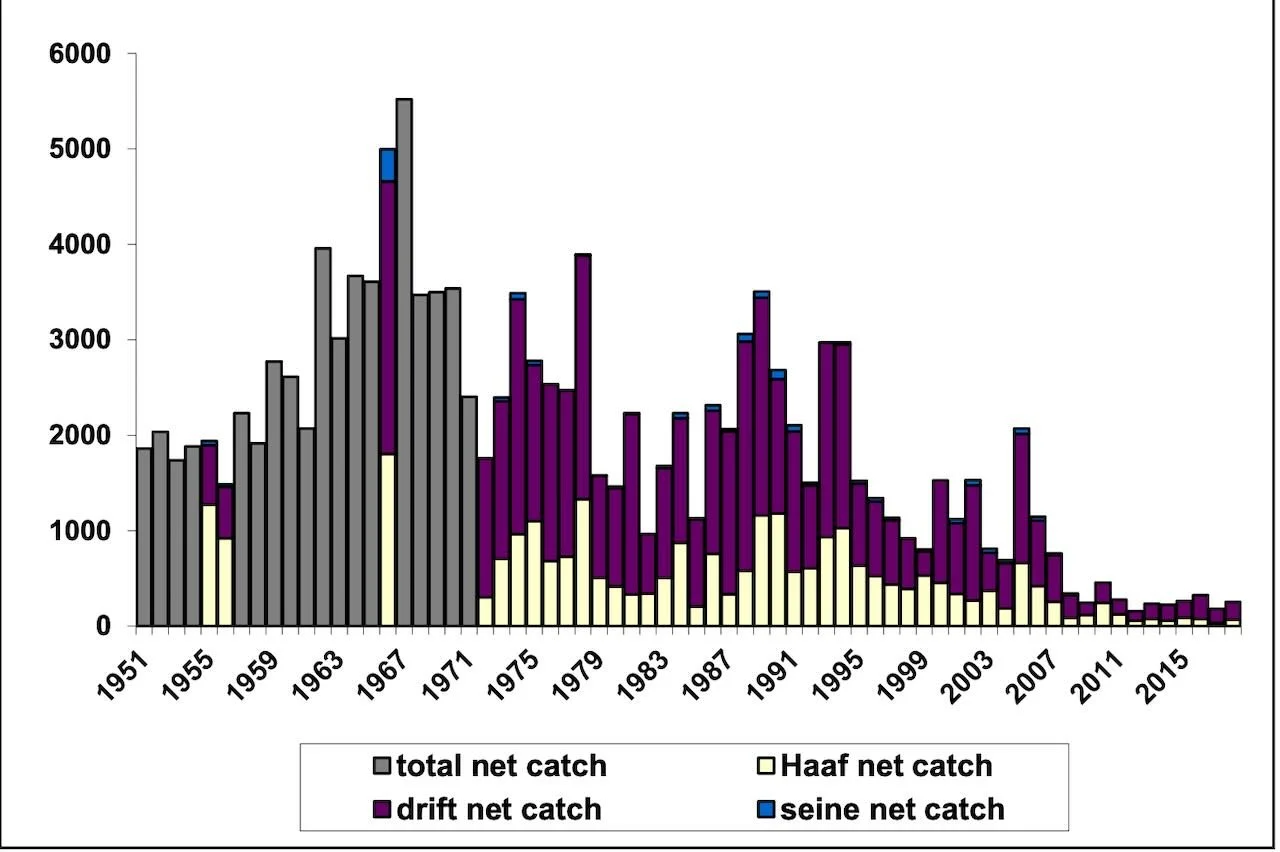

This chart illuminates the dramatic change. It shows the number of fish caught in nets in the Lune during the summer fishing season on a yearly basis.

Whilst there is considerable variation between years, there has been a sharp decline of net catches from a yearly average 3000 fish in the 1960s (with a high of c6,000 in 1968), falling to a yearly average as low as 300 salmon caught in the ten years up to 2018.

Lune estuary net catch of salmon 1951 to 2018: Courtesy Environment Agency

Note: Prior to 1999, the Lune supported 37 net licences, fishing over a five-month fishing season - April to August. Since 1999, only 19 licences were issued with the fishing season reduced to four months.

Typically, whammel nets account for two thirds of the fish caught, with Haaf netting around a third.

Tom Smith landing a salmon, whammel fishing in the 1970s: Photo Alan Smith

James Walker haaf net fishing 2023: Photo Tessa Bunney

Overfishing?

The EA state clearly it has not been net fishing, nor in combination with anglers, that has caused this calamitous decline in the river. Historically only a small percentage of fish entering the River Lune are caught in nets, perhaps averaging no more than five or six percent.

They make this statement.

‘The fisheries themselves are not likely to be the cause of the current poor performance of stocks. The prevention of killing of salmon will not, on its own, be sufficient to make up the current deficit in the number of spawning adults’.

Conservation Management

The EA do keep detailed and comprehensive annual records of salmon returning to home rivers in England and Wales. Frustratingly, Lune information is missing as the Forge weir fish counter at Halton has been out of action for some years and is not planned to be repaired until summer 2024.

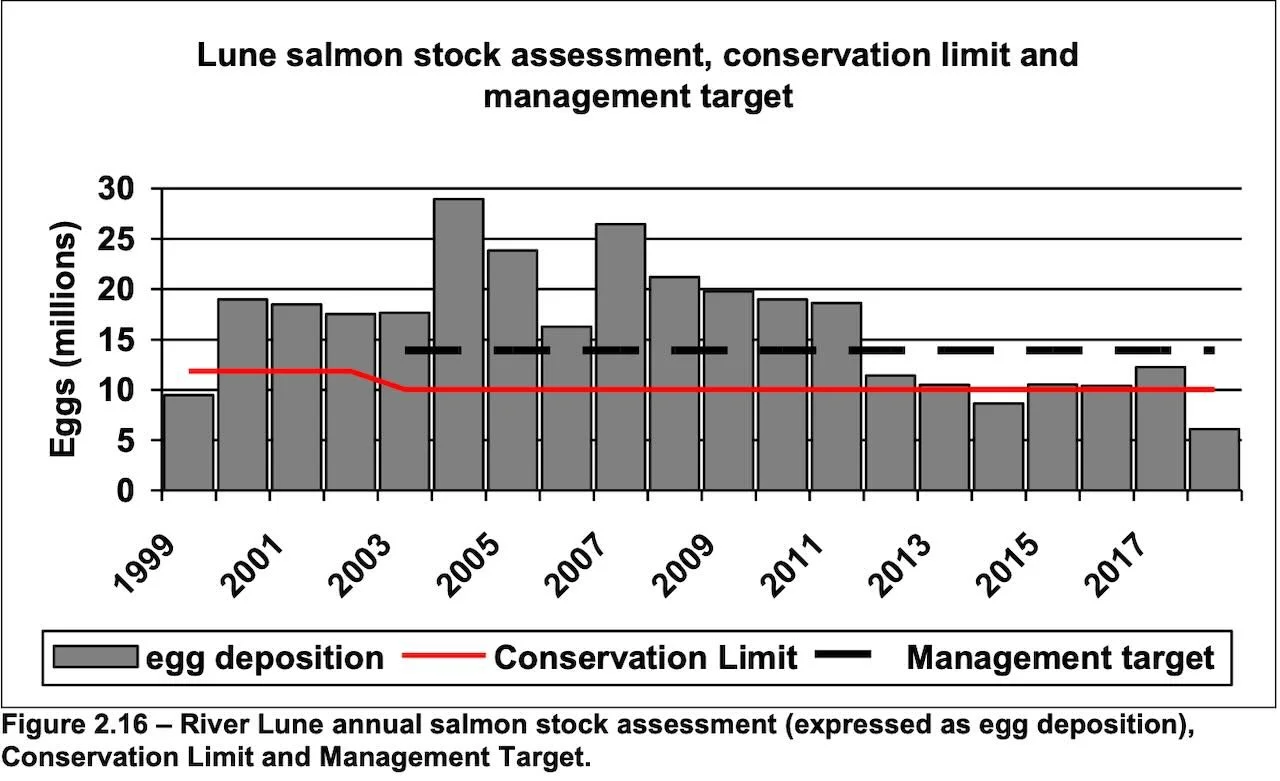

However, and perhaps more importantly, comprehensive information is collected on estimated numbers of eggs deposited by female fish returning to the spawning grounds in the tributaries of rivers.

And it is on these rates of egg deposition that conservation targets are based.

The map below identifies the main tributaries of the river Lune.

The Lune catchment area and the tributary rivers where salmon spawn: Courtesy Environment Agency

For each salmon river the EA has set a conservation target and conservation limit. The conservation target is higher, and it is at this level the stocks of fish are considered self-sustaining. The conservation limit is the flashing red alarm of dangerously low stocks.

Since 2003 the conservation target set by the EA for the Lune is 13.9 million eggs, this has not been achieved since 2012. The conservation limit is 10 million eggs, achieved in three of the six years to 2019.

Not just the river Lune

The sharp decline in salmon stocks is not restricted to our river. Almost all rivers in Britain, Europe, and North America, where the breeding cycle of salmon includes the long migration to feeding habitats in the Atlantic Ocean, are affected.

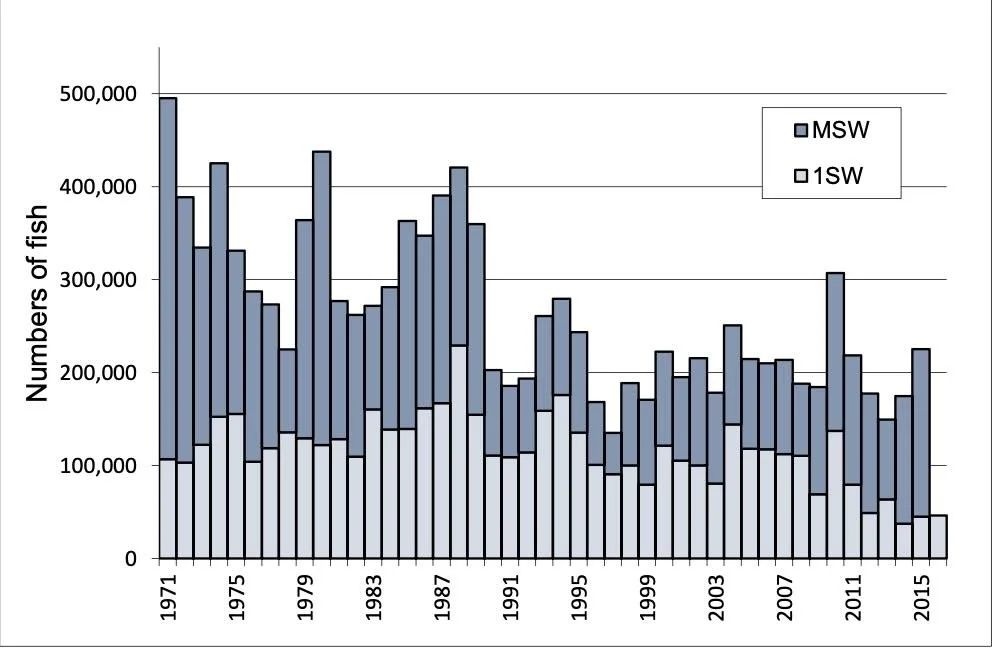

For England and Wales, it is measured as ‘Pre-fishery abundance’, that is the quantities of fish making their way back into the Atlantic split between the young fish (grilse) in their first sea winter (1SW) and older, mature fish (MSW)

Estimated Pre-Fishery Abundance (PFA) of salmon from England and Wales, 1971 – 2021: source Environment Agency.

This shows that the total of salmon from England and Wales has declined by around 50% from the early 1970s. Although there is some stability, even growth in the mature fish, the rate of decline of all-important young fish continues.

The latest data set published by the EA in September 2023 shows a worsening picture. In the gloomy summary they report that of the 64 monitored salmon rivers in England and Wales only 8 are assessed as achieving the conservation limit - which is the lowest ever recorded in the 30-year time series.

The one crumb of comfort in the depressing report was ‘a number of rivers in southern England, however, stocks had stabilised and then more recently shown signs of recovery’.

Drilling down we found the latest data for the river Lune. Although showing an improvement over 2021, the egg deposition rate was only 35% of the minimum limit for the signal of a healthy stock (in 2021 it was only 19%). The river remains ‘At risk’ and is forecast to remain so until at least 2027.

Of international concern

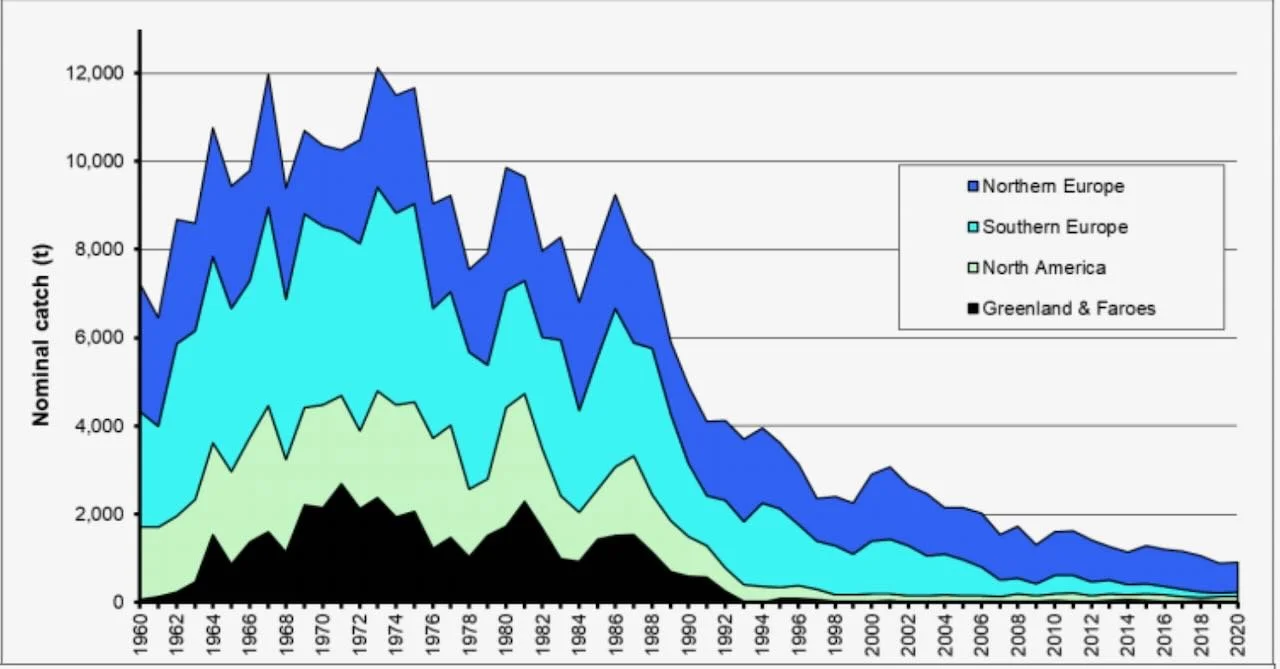

This chart shows the full picture of sharp decline of salmon catches on both sides of the North Atlantic. The significant fall off around 1990 is extraordinary.

Assessment of North Atlantic salmon catches: Source North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation

Why?

Recognising an international problem, The North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization (NASCO) was established in 1984. This enables Governments - the USA, Canada, Denmark, Russian Federation, the European Union, and the UK - to co-operate to conserve wild Atlantic salmon.

Summary of factors accounting for the decline.

NASCO identifies six key factors; industrial Pollution draining into rivers and sea, and in precipitation is considered one of the most important, as is the warming effect climate change. The impact of Invasive species, diseases and parasites and Ill-advised restocking programs have been harmful to wild populations. Habitat degradation where activities such as intensive agriculture and gravel extraction can alter the river’s structure. And finally, the increase in Predator activity of birds, other fish and mammals who have salmon as a food source, where their natural numbers may have increased due to human activity.

The Environment Agency were pressed for their view. They kindly provided this reply.

‘While the decline in numbers of adult salmon returning to our rivers over the last 60 years is clear, actual proven precise causes of the decline is not.

Currently about 5% of the young salmon that leave our rivers in the spring make it back to the rivers as adults, whereas 40 or 50 years ago that survival was in excess of 20%.

This decline is common across the whole Northeast East Atlantic area.

Unfortunately, research on salmon at sea is relatively recent, we don't have descriptions of baseline marine conditions from the 70's and 80's when survival was higher. This makes comparisons difficult. However, we can make some valuable and valid inferences though.

For example, in the west Norwegian sea where our salmon initially go to feed, there is a very marked increase in the abundance of herring, mackerel, and blue whiting over the last 10 to 15 years. This suggests a lot more competitors for the food that the young salmon feed on.

Also, in the last 10 or so has been the appearance of two new and seemingly unrelated health problems in the adult salmon as they return from the sea - Red Vent Syndrome and Red Skin Disease.

A recent scientific paper from Norway has compared over 30 years the growth of salmon at sea with the distribution and abundance of plankton in the main salmon feeding areas over the same period. The study identified a clear reduction in growth of salmon at sea in 2004, associated with a 50% reduction in zooplankton.’

Local Observation

There are a few committed individuals who occasionally fish in the river for sea trout with Haaf nets. Their experience from standing in the river catching – and returning – salmon, suggest the numbers are increasing slightly.

Understandably, they are strongly pressing the EA for the repair of the fish counter at Forge Weir to record exact numbers.

James Walker catches a fish: Photo Tessa Bunney

James removes the salmon from the net and returns to the river: Photo Tessa Bunney

Future Prospects, reasons for hope.

There is huge international support on both sides of the Atlantic for conservation measures to contain the decline and introduce measures to re-establish populations of salmon able to support sustainable fishing. For example.

Fishing for salmon in international waters has been eliminated for non-NASCO members. There have been no sightings of vessels fishing for salmon in international waters since the early 1990s.

All NASCO countries have implemented regulations to ban fishing when numbers fall below conservation limits.

Much stricter controls on farmed salmon have been introduced to contain diseases and the infestation of sea lice.

Major programmes to clean rivers of acidification have been introduced with particular success in Norway.

Equally successful, has been the clearing the routes upstream for salmon to spawn through new by-passes to hydropower scheme dams, in New England, USA.

On the river Lune

Upstream: Lune Rivers Trust

Recently established (2013) is the ‘The Living Lune Catchment Partnership’ dedicated to the conservation, protection, rehabilitation, and improvement of the river Lune. There are 32 members of the partnership ranging from the local authorities within the boundaries of the river, United Utilities, The Lune River Trust, Environment Agency, Lancaster University, the National Farmers Union, and local angling associations.

They identify the common themes, water quality – the impact of various pollutions and acidification. Barriers to fish routes – multiple obstacles are identified and are being overcome. Habitat degradation - planting trees to increase shade and improve the stability of the river bank.

The commitment is impressive. however

‘There is stark news for the world’s fish in the latest species reassessment by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published on 11 December, the report shows that nearly a quarter of the world’s freshwater fish are at risk of extinction, with the main UK population of Atlantic salmon reclassified as endangered’

Finally

Locally, nationally, and internationally there is comprehensive analysis on the decline, there is significant theoretical propositions as well as factual knowledge on the causes, and many fundamental reforms put in place. But it remains depressing there is so little evidence of return to sustainable numbers of this majestic fish.

Pictish stone carving of a salmon c300-900 AD: Photo Jessica Spengler, courtesy Environment Agency.

Many thanks to the Environment Agency, Alan Smith, Tessa Bunney and James Walker, also to Scott Wilson for editing assistance..