The Lawson Family of Sunderland Point

Tracing the Roots of a Quaker Legacy

Part one

Many will be familiar with the story of Robert Lawson of Sunderland Point. Indeed, those who have read my books or Hugh Cunliffe’s “The Story of Sunderland Point” may recognise him affectionately referred to as “our Robert Lawson.” For the benefit of new readers, I will use the same name—our Robert—to distinguish him from his uncle, Robert Lawson of Lancaster (1652–1736).

A Family Rooted in Two Worlds

Our Robert Lawson was born in 1690, the son of Joshua and Mary Lawson, a family based in Lancaster. Joshua and his brother, Robert, were well-known merchants and among the earliest to pioneer the transatlantic plantation trade. Between 1689 and 1691, Robert Lawson of Lancaster provided war transport for troops and equipment to Ireland, supporting William III in his conquest over the followers of James II and the Stuart dynasty.

Joshua also served as a sea captain, perhaps using Sunderland Hall at the Point as his base. From here, they would unload cargo, often tobacco or sugar, brought in by ship and arrange for its onward transport to Lancaster in smaller boats and by horse and cart.

Sunderland Hall (or Old Hall) – A photograph by Alan Smith

Joshua often appears in the Lancaster Port Books. These records show him captaining voyages to Virginia in 1698, Barbados in 1699, and again in 1700. In 1701, he was on trading voyages to Portugal and Norway—a reflection of the far-reaching maritime networks that defined the region’s economy during this period.

Evidence of Joshua’s commercial activity also appears in The Autobiography of William Stout of Lancaster, a wholesale and retail grocer, ironmonger, and fellow Quaker. In 1698, Stout recounts how he agreed to take a one-sixth share in a new ship, the Imployment (or Employment), then under construction at Warton (near Carnforth). Stout personally sourced masts, sails, rigging, anchors, and cables in London and arranged for their shipment aboard the Edward and Jane, a ketch captained by Thomas Thorp.

Stout then took up lodging with Joshua (probably) at Sunderland Point for several months until May 1698. During that time, he helped complete and outfit the new vessel for a voyage to Virginia, finishing the preparations by October.

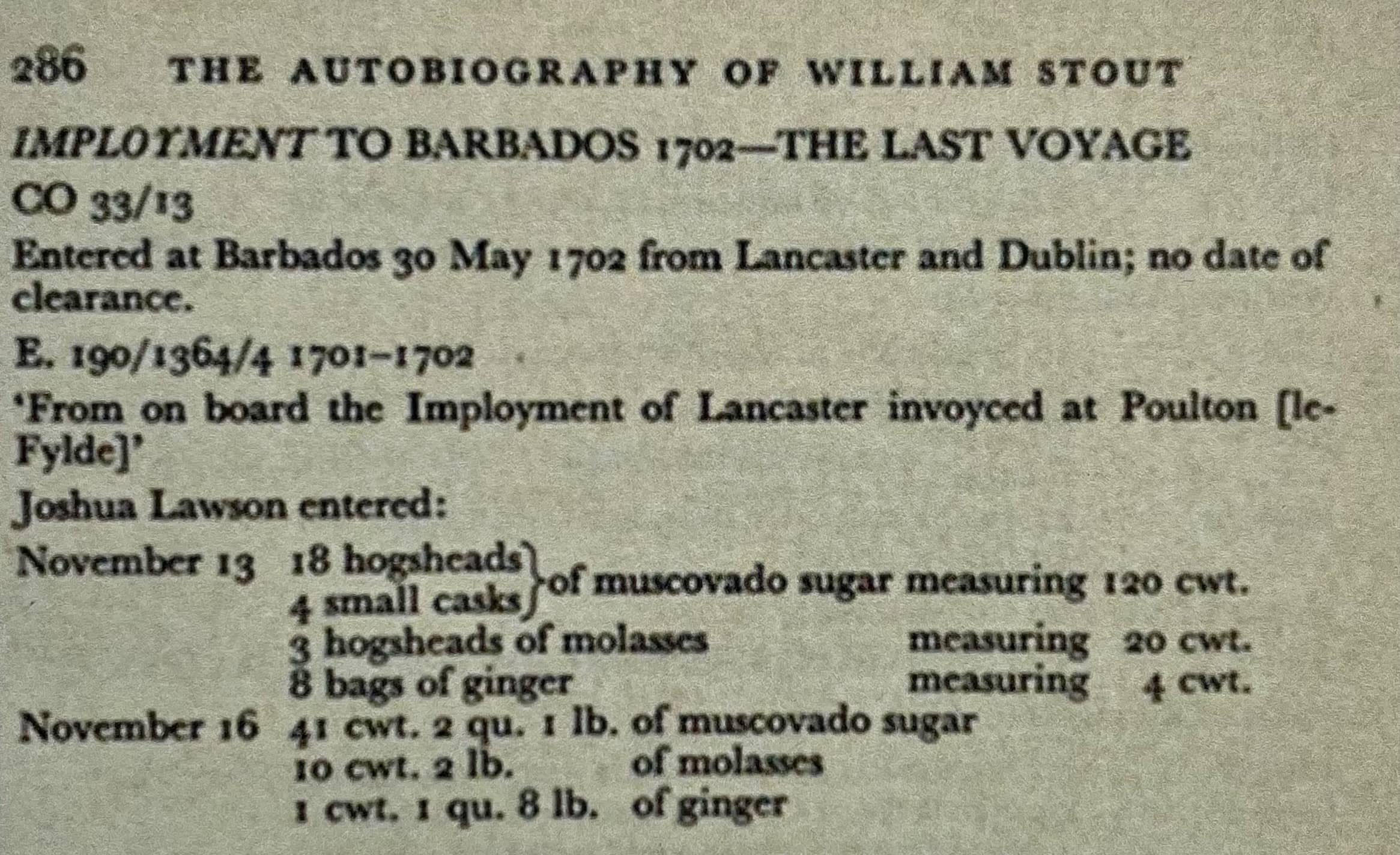

Here we see a cargo of Sugar for Joshua from the last voyage of the ‘Imployment’

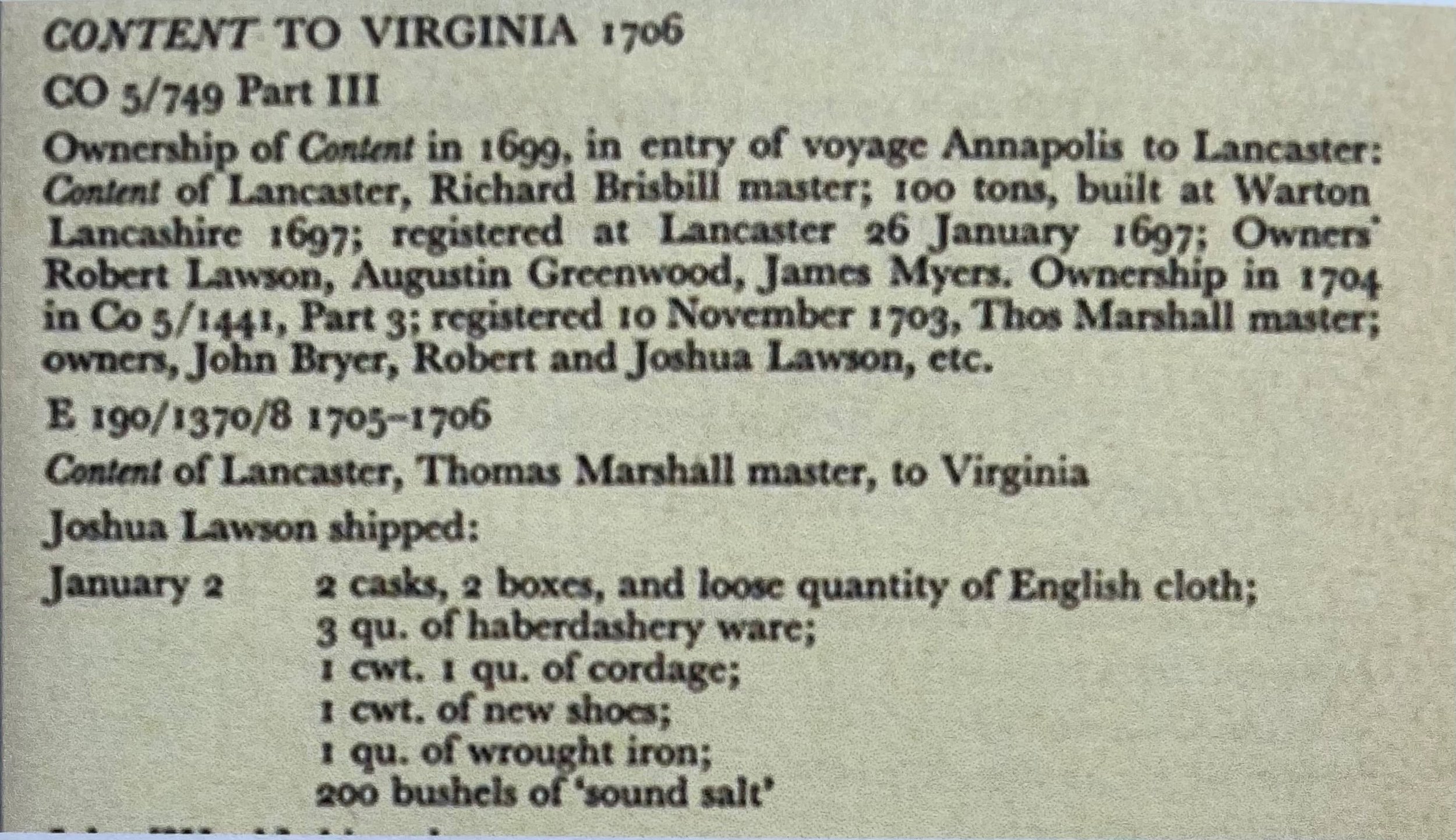

Here is a voyage of the ship “Content” in 1706. Joshua is stocking his warehouse and sending goods overseas. Robert of Lancaster and his brother-in-law James Myers were part owners since at least 1697.

Both shipping records from the work of M.M. Schofield and R Craig.

After 1703, he had given up his Captaincy and was working more closely with his brother Robert. In 1704, Joshua (accompanied by William Stout, who was on a trip to London) visited Warrington, where he had a son at Gilbert Thompson’s Quaker school. The Son is unnamed; dare we assume this was the now-14-year-old “our” Robert Lawson, a possibility we may never know for sure.

An armed British merchant ship of the early 18th century: Internet stock

Back in Lancaster, Robert and Joshua were both members of the Lancaster Meetings of the Friends with tasks assigned to them. From the Journal of the Friends Historical Society, we learn that when looking for a schoolteacher – Joshua Lawson and Thomas Wilson “were appointed to take care that the schoolmaster be diligent in educating his scholars and keep them out of anything that would corrupt them.”

The Friends Meeting House Lancaster opened in 1708. Lancaster Quakers website

In 1708, William Stout and Robert were assigned the job of building a new Meeting House. Also in that year, Robert twice went to London to aid the “dissatisfied” Friends in their Solicitations for an easier Affirmation. (To take office in local government, you had to swear on the bible; the Quakers disapproved of this)

A Story Lost to Fire—and Pieced Back Together

Much of Joshua’s life remains a mystery. Despite numerous searches, I found no trace of his baptism or marriage. Knowing that Joshua was a Quaker, I turned again to the Friends' records, where I discovered a tragic loss: in 1851, local youths broke into the Lancaster Meeting House, forced open the chest containing the Quaker records, and set them alight. Much of the historical archive was destroyed in the fire. Nevertheless, I did find entries for Joshua’s children in the surviving Friends’ registers, which confirm that his wife’s name was Mary.

The Wilful burning of the records, Lancaster Gazette, 10th May 1851: Courtesy Guardian Newspapers

In the early 18th century, Lancaster was a town gripped with fear. In 1715, political unrest swept through the region as the Jacobites rallied to restore the House of Stuart to the throne. A large Jacobite force was moving south from Scotland, with Lancaster directly in its path. In the tense days that followed, government troops scoured homes in Lancaster, hoping to seize weapons.

Attention turned to a ship jointly owned by Robert of Lancaster and William Heysham —The Robert—then moored at Sunderland Point. The vessel, well-armed with cannon, drew concern. Robert was warned that the cannons and small arms aboard would be prime targets for the Jacobite soldiers and was told to move the vessel out of reach. He refused—and paid the price.

The Highlanders seized the ship's guns. Ironically, these weapons could also have aided the town’s defenders, but Robert refused to part with them. It's worth noting that, as a Quaker, Robert was not supposed to arm his ships at all, though in practice, many Quaker merchants quietly did.

A New Generation: Robert Lawson of Sunderland Point

While Robert of Lancaster faced the pressures of war, his nephew, our Robert Lawson of Sunderland Point, was beginning to establish his legacy. In 1716, at the age of 26, he married Mercy Moss at the Quaker Meeting House in Manchester. This marriage linked the Lawsons with the Moss family, a respected Manchester Quaker family with growing maritime interests. Mercy’s father, Isaac Moss, co-owned with Robert of Lancaster and our Robert a ship named the Lancaster, built at Sunderland Point.

A report from the Quaker registers says (edited):-

Whereas Robert Lawson, son of Joshua Lawson of Lancaster, merchant and Mercy Moss, daughter of Isaac Moss of Manchester in the County of Lancaster, spinster, have declared their intentions of marriage with each other before several publick meetings of the people called Quakers in Lancashire.

The Marriage 1716

We are fortunate to have this eyewitness account of the actual marriage. We are with them as they hold hands.

Robert Lawson and Mercy Moss appeared in a solemn and publick assembly of the aforesaid people and others met together in their publick Meeting House in Manchester, and in a solemn manner according to the example of holy men recorded in the scriptures of truth, he the said Robert Lawson taking the said Mercy Moss by the hand did openly declare as followeth, viz, In the fear of God and in the presence of you take this my dearly beloved friend Mercy Moss to be my wife promising to be unto her a kind, loving and tender husband until it shall please almighty God in his infinite wisdom by death to separate us.

And there in the said assembly she the said Mercy Moss did likewise declare; In the presence of the Lord and before this assembly I Mercy Moss take Robert Lawson to be my husband promising to be unto him to be a loving faithful and obedient wife until it shall please the Lord by death to separate us. And the said Robert Lawson and the aforesaid Mercy (according to the custom of marriage) now Mercy Lawson as a further confirmation did then and there to those present set their hands and we whose names are here unto subscribed being present amongst many others at the solemnising of their marriage and subscription in manner as witnesses have also to those presents subscribed our names the day and year above written.

Signatures to the wedding: From the Quaker records, Ancestry

After their marriage, they returned to Sunderland Point. We believe they moved into the Old Hall.

The younger Robert followed in his father’s footsteps as a merchant, trading across the seas. With his growing wealth, he chose to invest in the maritime facilities at the Point. According to Hugh Cunliffe, in the years following 1715, he constructed two large warehouses, an anchor smithy, a block maker’s shop, and a ropewalk These developments enabled shipbuilders to fully outfit vessels locally, thereby avoiding costly and time-consuming journeys to London to source equipment.

The two warehouses were adjacent, three-storey buildings. Probably what is today 13 and 14 on Second Terrace.

Number 13 on the right with the white door and 14 next door with the exposed porch and bay window: Photo Ted Levey

Hugh also believes that the Big House, now occupied by the Reading Rooms and two apartments, was possibly the home of Robert’s parents, as there is a stone near the door marked L. IM 1715. He says I and J were interchangeable (in what they call secretary hand), and feels it must refer to Joshua and Mary Lawson.

The date stone: Photo Lynne Levy

Improving Navigation and Trade

By 1720, the merchants of Lancaster focused their concerns on the dangerous sands at the mouth of the River Lune. They petitioned the Lancaster Corporation to fund the placement of a buoy at the shoulder of the Lune sandbank to help guide vessels through the shifting channels. The following year, the Corporation pledged £20 toward the effort on the condition that the merchants prepare a replacement buoy when needed. Among the signatories of the subscription list were “Joshua and Robert Lawson of Sunderland Point” (father and son), who jointly contributed £5, and “Mr Robert Lawson of Lancaster,” who gave a further £5—a fitting testimony to the Lawson family's commitment to maritime enterprise and local infrastructure.

Financial problems

In 1720, Robert of Lancaster came close to bankruptcy, losing a great deal of money in the South Sea Bubble (a spectacular financial crash). William Stout had cautioned him to withdraw or sell but hadn’t done this, and when the collapse came, he lost heavily. However, the considerable value in his Will at the time of his death suggests the rapid recovery of his fortunes.

In 1728, our Robert did become bankrupt. And William Stout had something to say about that, stating, “Robert Lawson of Sunderland failed in his credit who had done as much in merchandise here as all the rest and had good success in trade - but imployed the profit in superfluity of buying land at great prices and building chargeable and unnecessary, houses, barns and gardens and other fancies. And costly furniture so that he overshot himself, and a commission of bankruptcy got out against him.”

Then, in the ‘Annals of Cartmel’, I find information from the Flookburgh Church records stating that Joshua and Robert Lawson borrowed £ 95 on a bond from the Chapel (Church). By 1728/29, the date of our Robert’s bankruptcy, the debt with interest had risen to £96 9s 7¾d. Robert eventually repaid £70 1s 7½d, leaving a loss to the Chapel of £26 8s 0¼d.

When declared bankrupt (which was considered a great disgrace in those days), our Robert’s debts were £14,000, a substantial amount in those days, but he did manage to pay his creditors 14s in the pound. He spent the rest of his life living on Sunderland Point.

While much has been pieced together from surviving Quaker records, gaps remain. There is no record of Mary Lawson, Joshua’s wife, in the Quaker registers. One possible explanation is that she never formally joined the Society of Friends. A burial entry at St Mary’s Church, Lancaster, records that a Mary Lawson, wife of Joshua, was buried there on 24 May 1716. Her place of residence was listed as Lancaster.

Joshua Lawson himself died on 13 January 1726 (recorded as the 13th of the 11th month in Quaker notation) and was buried on the 16th at the Quaker Moorside Burying Ground. His brother, Robert Lawson of Lancaster, died ten years later in 1736 and was laid to rest in the Meeting House Burial Ground in Lancaster.

Complaint about the Causeway

In the Lancaster Gazette of May 7th, 1892, is an item taken from a 1731 edition of the newspaper, which refers to a legal challenge over the state of the road by Mercy. I wish I could, but sadly, I have not been able to find any further information about this.

July 16th Sessions Day – The King against the township of Heaton with Oxcliffe for not repairing their highways- at the instance of Mrs Lawson – Sunderland.

Final Years – Death of Mercy in 1770

Mercy was buried in the Quaker Yard in Lancaster.

And our Robert

Robert Lawson of Sunderland died on the 7th January 1773 and was buried at Lancaster on 10 January 1773. Whilst it is not said, I am sure he would have been buried as a Quaker in their yard at the Meeting House.

Both extracts from the Quaker records, Ancestry

This brief glimpse into the lives of Joshua and the two Robert Lawsons reveals their prominent role in the maritime trade of the time while also situating them within a close-knit network of Quaker businesspeople and shipowners whose influence significantly shaped Lancaster’s economy and culture.

Next week, in part two, Beth explores the extraordinary story of how Lawsons became among the first Quakers in Lancaster. And why John Lawson is remembered as one of the “Valiant 60”

In Book 2: Sunderland Point – The Early Days, Beth explores the lives of ‘our Robert,’ his wife, Mercy Moss, and their children—a story that is both compelling and deeply poignant. Their lives, like so many of their generation, were marked by hardship: early deaths, failed enterprises, illness, and the upheaval brought on by war, politics, and religious dissent.

If you would like a copy of any of the books, they are available at a modest cost by contacting Lynne Levey at lynne.levey@icloud.com

(or again as digital copies at £5 from Beth via email beth.hampson@hotmail.co.uk)

Lynne also has copies of Hugh Cunliffe’s History of Sunderland Point.