A Narrow Escape from Drowning

John Hopkinson in later life: From the collection of Alice Barrigan

On Saturday, 9 August 1862, John Hopkinson, aged 38, a professional engineer from Manchester, was returning to Sunderland Point to rejoin his large family. They had first arrived the previous Monday (4th August) for a holiday.

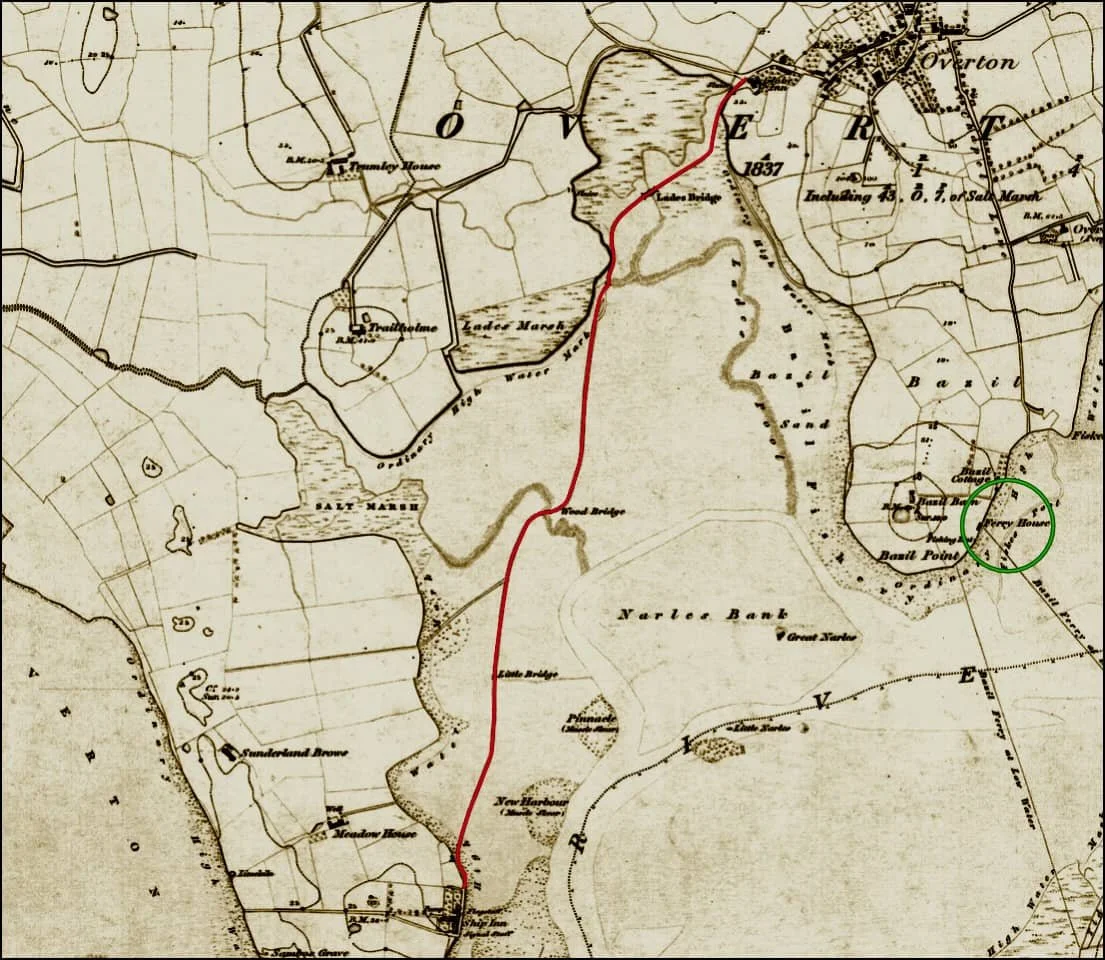

After leaving the train at Lancaster, he took a boat to Overton. For unknown reasons, he had misread or miscalculated when a fast-moving tide would reach the road.

The landing stage at Overton (green) and the causeway (red) on the 1840s Ordnance Survey Map: Courtesy National Library of Scotland.

The Tidal Causeway

Taken from his notes written at the time, this is what happened later that day.

‘I took train in afternoon to Lancaster and boat part way down the river, landed near Overton to walk to Sunderland – same road over the shore as our bus had taken on the Monday. The tide was coming up … I walked as rapidly as I could towards Sunderland Point through the gradually rising water which covered all the road. I saw a stake standing and, supposing that it might be to mark the road, made for it …

I felt with my feet the ruts of the wheels and knew it must be on the road. I called continuously: "Boat ahoy. Boat ahoy." The water continued to rise above my hips so I unbuttoned my waistcoat and put the left flap over my shoulder to keep my watch dry and I felt the run of the tide past me and dare not leave the stake as I would have been carried off my feet … My voice failed with shouting but a handful of water restored it.

And at last had the great relief of hearing the handling of the oars of a boat putting off. I shouted to direct the boat where I was. They rowed with a will, were soon alongside and seized hold to haul me in.

The water was near my armpits and probably at the top of the tide.

I learned that a woman, ironing her husband's shirt with the cottage window open, had heard my shouting and ran to tell the boatmen to get the boat out. John (his son) was on the shore, knew my voice and that I was taking the shore-road from Lancaster, and knew that I must be in danger. The boatmen were sure that the voice must come from the opposite shore. My boy insisted on their going towards Lancaster. And he was right as they soon found”.

It’s not hard to imagine that Alice, John’s wife, must have been in considerable distress. In her care were their eight young children, ranging in age from John, who was 13, to the youngest, Gertrude, just three months old. Alice had the support and comfort of a mother’s help, a nurse for the children, and 25-year-old Emma Wood, the cook.

John, possibly in 1862, with daughters Ellen and Mary aged 8 and 5: From the collection of Alice Barrigan

We can sense her relief when John returned and imagine him giving reassurances that he was not really in any great danger, and that they should look forward to continuing their holiday.

The Lancaster Gazette

And that might have been the end of it, except for an extraordinary (and long) letter which appeared a week later, on Saturday, 16th August, in the Lancaster Gazette.

It was written by Jos. Swainson Junior, a young man from Kendal. Joseph was a trainee solicitor and staying at The Hotel on Second Terrace (now number 14), then in the tenancy of Yorkshire-born farmer Richard Nicholson and his wife Jane.

Sir, perhaps you will allow me to trouble you with the following narrative of a very narrow escape from death by drowning which has just occurred here.

About ten o'clock on Saturday night last Mrs Nicholson, the wife of Mr Richard Nicholson, who farms this property, having occasion to go to a neighbour's house on the other Terrace, heard cries of distress which appeared to proceed from the direction of the road across the Sands to Overton. She immediately gave the alarm to myself and her husband, and the nearest boatman having been at once roused, a boat was with all possible haste procured, and in the absence of a fourth experienced boatman, I most willingly accompanied them to pull the fourth oar.

The cries of distress which were borne along the water to us were truly pitiable, and such as to call forth the most strenuous efforts on the part of the men. We proceeded as rapidly as possible in the direction from which the cries came, and when approaching the post which indicates the first small bridge on the road to Overton, we found a gentleman up to the chest in water clinging to the post in an all but exhausted state.

On our return, after drawing the gentleman in safety into the boat, we found that he was a Mr Hopkinson, from Manchester, whose wife and children, are staying down here for a few weeks, and who were all, with the exception of his eldest boy, in happy ignorance of the occurrence.

He was on his way from Lancaster, having arrived by the evening train, with the intention of spending Sunday at this place. The tides at this time rise very rapidly, and the boatmen all say, that there cannot be the slightest doubt as to the fate of this gentleman had the boat been longer than five or ten minutes in reaching him, for, in addition to the great increase which that period would have made to the water (it still being an hour and a half from high water) it would have been impossible for Mr Hopkinson, judging from the weak state in which we found him, much longer to have retained his hold.

The rescue of this gentleman from a death gradually but certainly approaching, was no doubt due, under Providence, primarily to the mere accident of Mr and Mrs Nicholson's not having gone to bed at their usual early hour, and also to the strenuous efforts of Thomas Dickenson, James Spencer, and John Bagot, with whatever assistance I may have afforded. The persons who live in the cottages which are nearest to the place where this occurrence happened, were not aware of it until next morning.

The road between this place and Overton, when the tide is out, is almost as safe and hard as any turnpike, but when covered with water it is of the most dangerous description, from the many and deep pools which abound near to it.

My reasons for troubling you with this narrative is that a warning may not be lost to strangers of the extreme imprudence of venturing across the sands without first ascertaining the state of the tide, especially at night time. And, also, that I may redeem a promise made to the men that I would do my best that the great anxiety to do their utmost and the strenuous exertions they made should not be lost sight of.

PS - The boatmen here have often before been instrumental in saving lives”

Reading this, Alice must have re-lived the incident and wondered how close she had come to becoming a widow. She wrote to John, perhaps crossly, annoyed she provided the account for Jos to embellish:

"It is just a worked-up tale. Had I seen that letter, I should have kept at a more convenient distance from Mr Swainson and deemed him a young puppy who wished to appear in print …’

Well, is it just a ‘worked-up tale’?

Had Joseph painted himself into a heroic role? Both the letter and John’s notes of the event are almost identical, suggesting authenticity. So, do we accept that Joseph was in the boat as he claims? Or had he picked up the story from Alice directly, as her note to John suggests.

The Rescuers

The three were highly experienced fishermen and probably river pilots. Thomas Dickinson, aged 60, one of a large family occupying several properties at the Point, lived at Cotton Tree Cottage (number 20). James Spencer, 34, had spent his entire life in the village and had just moved into Upsteps Cottage in the Lane. John Bagot, another 60-year-old, lived in Preesall, a fishing village further down the coast. (His son Richard would later move to Sunderland Point into number 4 when he married Millicent Gerrard.)

James Spencer c1890 and Upsteps cottage c1914: From the collection of Hugh Cunliffe

The rescue boat, a fishing vessel, would have had two pairs of oars. If speed were essential, two of them would each handle a pair of oars. Since this would require facing away from the direction of travel, the third man would have been at the back of the boat, standing, searching for John and guiding the other two.

John admits in his account that he was in great danger: “I felt the run of the tide past me and dare not leave the stake as I would have been carried off my feet”

Given the urgency, having four in the boat, with each taking a single oar and one being inexperienced, is highly unlikely.

However, it would be unfair to comment further, and we should leave it at that, but there is one more twist to this story.

The Lancaster Observer

A grumbling letter of complaint appeared a little later in the Observer on Sunday, August 16, suggesting that for taking part in such a courageous rescue, the three men had not been ‘suitably rewarded’ by John Hopkinson.

Swiftly, the following day, Jos. Swainson wrote again to the Gazette. His letter is a vigorous defence of John.

Sir, A paragraph in last Saturday's Lancaster Observer having been pointed out to me, stating that Mr Hopkinson had not thought fit to reward the men for their exertions, I venture to trouble you again to contradict a report that John Hopkinson had not rewarded the boatmen.

So far from being the case, Mr Hopkinson has rewarded each of the men most handsomely, in a much more suitable manner than by a pecuniary recompense, and, moreover, in a way which will afford a lasting memorial of his appreciation of their prompt and efficient exertions.

Well, were they suitably rewarded?

The causeway was notoriously dangerous. In 1869, Henry Croft of Overton drowned crossing the road, as was William Seddon innkeeper of the Point’s Temperance Hotel in 1877. Rescues were numerous. In 1870, a farm boy from Sunderland Brows and two horses were rescued by fishermen. After saving the boy, they went back into the water up to their necks to rescue the horses.

Perhaps most famously, in 1896, a Char-a-bac from Morecambe carrying twenty visitors slipped off the road into a rapidly rising tide. Thankfully, all were rescued.

They were risking their own lives to save others. It was expected that something tangible, financial, should be offered.

Quite right too. So, what was the fuss about? John, a firm Congregationalist who had been active in his church since boyhood, will have discussed a suitable reward for the three men with Alice.

To remind John when he was in Manchester, Alice wrote:

“Do not forget the Bible for the boatmen; I fancy they look for some reward.”

An inscribed family Bible. Perhaps not quite what they were expecting, maybe not even close.

We are grateful that Alice Barrigan contacted the website to share this story. Alice is a descendant of John and Alice Hopkinson and provided more information about what happened to some of the children.

Young John, who had been out on the shore looking out for his father, would later be a renowned physicist and electrical engineer (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hopkinson). He and three of his children died in an Alpine climbing accident in 1898.

Alfred became a lawyer, academic, MP and first Vice Chancellor of Manchester University (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Hopkinson)

Charles was a consulting engineer in partnership with his father.

Edward became a civil, mechanical and elecrtrical engineer and an M.P (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Hopkinson

Alice also has a blogspot ‘The Engineering Hopkinsons’ which can be found at