Peter Hall in the Second World War

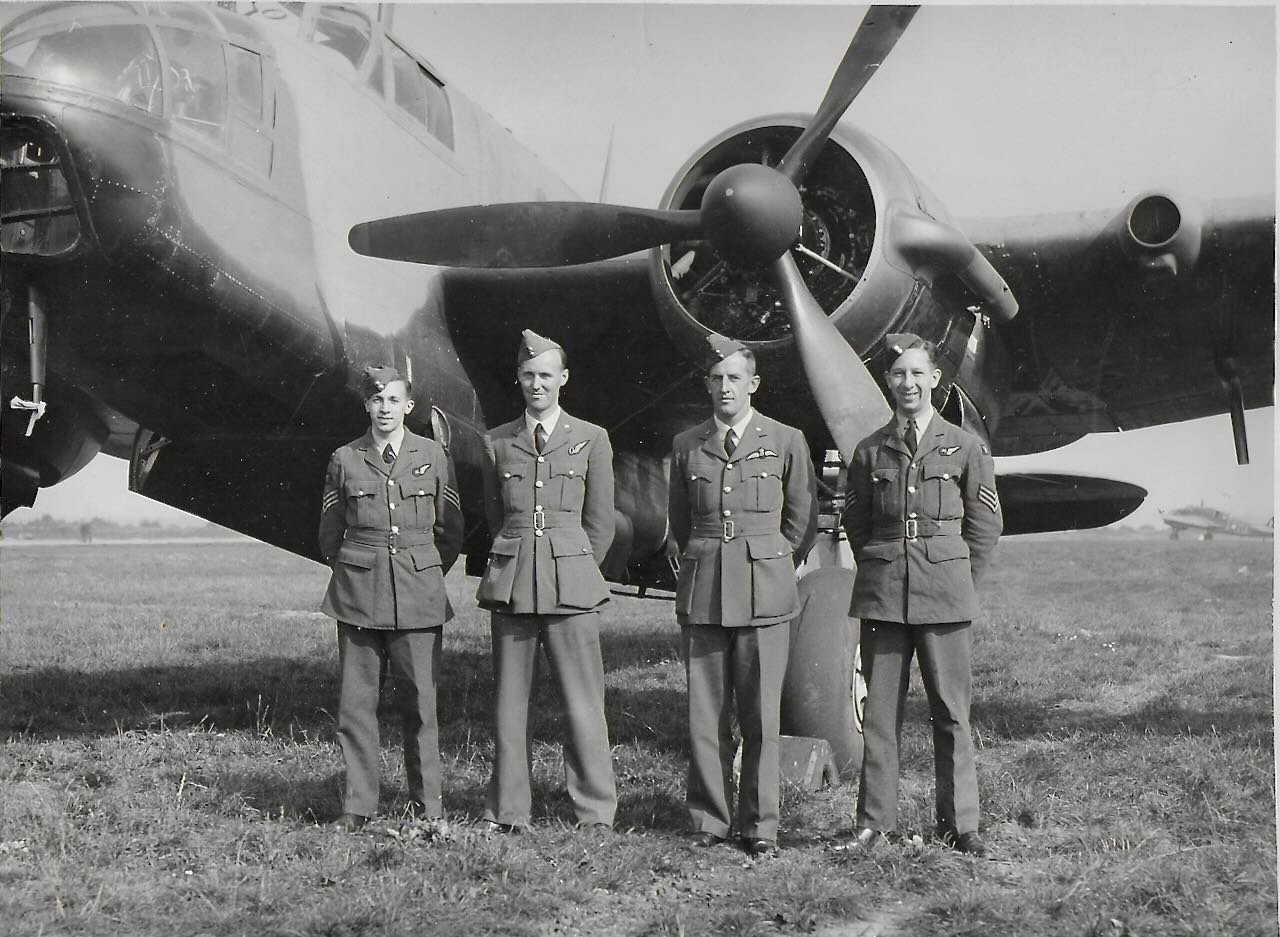

Peter Hall (2nd right) in front of a Bristol Blenheim Bomber at St Eval, Cornwall 1941: Courtesy Robert Hall.

Peter Hall was born in January 1911, the fourth child of John and Connie Hall. He grew up in Aldcliffe and attended the Grammar School in Lancaster and later Clifton College in Bristol.

Peter showed an early interest in flying and enrolled at the Lancashire Aero Club and was awarded a flying certificate in September 1932. After qualifying as an electrical engineer in London he worked for RA Lister in Dursley, Gloucester.

RAF service.

In October 1939, a month after war was declared, Peter enlisted in the RAF and was mobilised in May 1940. After flying training in which he achieved special distinction he was commissioned Pilot Officer and quickly promoted to Flight Lieutenant in November 1940.

In the summer of 1941, Peter was based at Chivenor (nr Barnstaple) where he met Dick Iliff who would become a life-long friend. The two were later posted to Squadron No. 22 first at Thorney Island (nr Chichester) and a few months later to St Eval in Cornwall. Peter was flying Bristol Blenheim bombers in sorties over France.

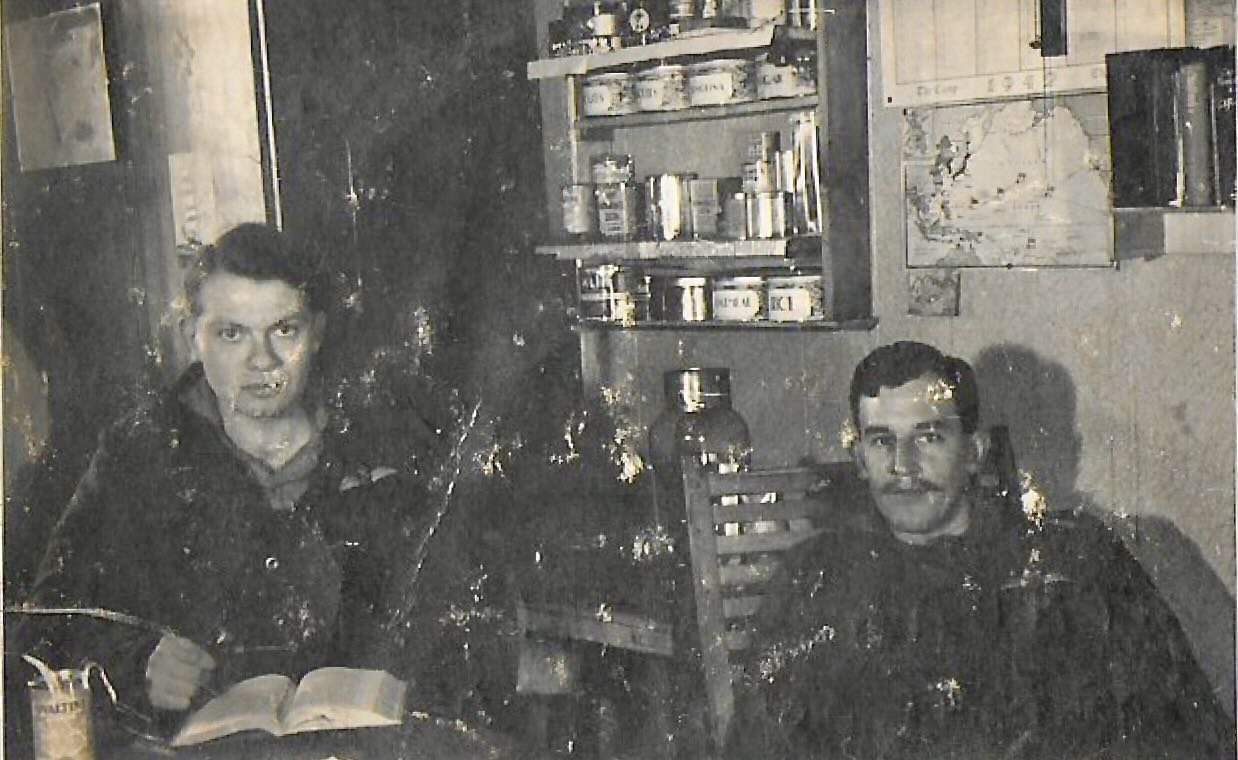

On 5th November 1941, his plane was shot down in the Bay of Biscay, killing two of the crew. Peter was quickly captured and sent to Stalag Luft 1, near Barth on the Baltic coast. A short time later Dick Iliff was also shot down and sent to the same camp. In April 1942, the entire camp was transferred to the newly built Stalag Luft 3 close to Sagan, Lower Silesia, now in Poland (Zagan).

Dick Iliff (left) and Peter Hall Stalag Luft 1 Dec 1941/ Jan 1942: Courtesy Robert Hall.

Stalag Luft 3 is well known from the films ‘The Wooden Horse’ (1950) an escape making use of a wooden vaulting box based on the book by escapee Eric Williams and more famously ‘The Great Escape’ (1963), which was loosely based on Paul Brickhill’s account of his time in the camp.

At its peak, Stalag Luft 3 - which was under the direction of the Luftwaffe - housed over 11,000 air force officers from allied countries; 2,500 were British. Within the prisoner group there was a strong sense of furtive obstruction and subversion. Newspapers were created, guards were baited, and prisoners began creating fake German uniforms and papers in preparation for an escape.

After the 1943 ‘wooden horse’ escape, a plan was hatched for a major breakout. Three tunnels were dug named Tom, Dick, and Harry. As the soil was extremely sandy, it was removed by filling long slender sacks which were hidden under their trousers to be released around campgrounds. These men were known as penguins.

Peter showed ingenuity to make imitation guns for two fellow officers dressed as German guards. He made the wooden framework for lining the escape tunnels and his own compass out of a plastic bottle top in preparation for escape. Although discovered during the event, 76 escaped that night in March 1944. Fortunately, Peter was not one of the escapers. Almost all were immediately captured and 50 were shot on Hitler’s personal order.

Peter’s daily life of a POW at Stalag Luft 3.

Breakfast: hot drink and 1 or two slices of German bread.

Morning roll call outside the huts, taken by a German officer.

After roll call, educational classes in many subjects and escape activities.

Lunch: sometimes soup or sauerkraut and 2 slices of bread supplemented by spreads and extras from Red Cross parcels.

Afternoon: Continuation of the morning’s activities.

Evening: after supper (same as breakfast), reading or bridge till 11.59. Lights out at midnight.

Once a week, parties of 30 or 40 POWs were taken under escort for hot showers.

In winter, skating on a home-made ice rink and watching Canadians play ice hockey. In summer, soccer, or golf on a home-made course with home-made clubs and balls.

RAF Officers at Stalag Luft 3. Peter Hall (3rd from left) Spring 1942: Courtesy Robert Hall.

Stalag Luft 3 had some of the oldest POWs and many had been prisoners for more than 3 years. With the collapse of the German war effort from June 1944, inmates at Sagan received only half - instead of the prescribed full - Red Cross parcel a week. As the diet was 1000 calories a day per below basic necessity, the physical standard of prisoners was seriously weakened. The years in captivity coupled with the shock of the brutal execution of the 50 escapees ensured some damage to mental health.

The end of imprisonment.

In late January 1945 with the Russians advancing from the east, the order was given for the camp to be evacuated. In the chaos of a sudden departure at least 23,000 Red Cross parcels, clothes, blankets, and books were left behind. An estimated 2 million cigarettes were left in the north and east compounds.

In what became known as ‘The Long March’ the transfer started in appalling cold conditions with 6 inches of snow on the ground. Prisoners and guards suffered from starvation in sub-zero temperatures, and many died by the time they reached the compound at Marlag-Milag in northern Germany.

Eventually, the remaining officers, yearning for normality after the privations of the last 3.5 years, were repatriated to the UK. Peter never spoke of his time as a POW. Nowadays, he would have been diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and received counselling.

Marriage.

Peter, who was friendly with Philip Gilchrist from Sunderland Point, met his future wife, Fiona Gilchrist, through tennis parties in Lancaster. After the war, Peter and Fiona were involved in farming work near Chichester in Sussex.

They were married in January 1947 and after moving to the Point into number 22 their son Robert was born in February 1948. In 1958, they moved next door into the Old Hall - number 21. Following the death of Philip Gilchrist in 1956, the Rev William Swainson and his wife Dora, who had been living in 21, moved to The Dolphin house.

Mowing grass at no 22 c1960: Photo Robert Hall.

Life at Sunderland Point.

Peter kept busy as a market gardener growing copious amounts of fruit and vegetables in the gardens of no 22 and 23. He also involved himself with a number of local groups and was a stalwart of the Overton Memorial Hall. He was famous for his tomatoes and exhibited at the Overton Horticultural Society Annual Show.

Outside no 21 July 1980: Courtesy Robert Hall.

Peter was a quiet, modest, self-effacing man who in later years took great interest in his grandchildren. He liked sailing on the river in the whammel boat Sirius bought in the 1960s from fisherman Bert Smith. He was also a member of the Lancaster branch of the RSPB.

He was a stalwart of the whist drives held throughout the winter months in the Reading room. New Year’s Eve was celebrated with a 24-hand whist drive, with refreshments after 12 hands. The evening was rounded off with a rendering of Auld Lang Syne as all linked arms to see in the New Year.

Fiona died in September 1973.

Peter was a lifelong member of the Congregational Church (later the United Reform Church) with many years at Sefton Road, Morecambe.

Peter died in August 1996.

Robert Hall October 2023.

We are grateful to Robert for writing and sharing this information about Peter.