Navigation into the River Lune-1737

British merchant vessel of 1762: Image credit: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Today’s yachtsmen and women with all their technology have to keep their wits about them sailing up the estuary, past Sunderland Point, going to Glasson Dock … but, as we will see, it was a huge challenge for the sailors of 300 years ago.

For centuries, it has been dangerously challenging to navigate through the multiple hazards of Morecambe Bay into the estuary of the River Lune. At a massive 10 metres, the tidal range of Morecambe Bay is one of the largest in the world and daily transforms the seascape.

Today, a sailor on a mid-sized yacht has instruments and navigational aids that provide precise positioning, speed, direction, water depth beneath the boat, and instructions to reach the destination. There are accurate tide tables and real-time localised weather forecasts, and an engine to use if the winds are unfavourable.

Modern Instrumentation: source Wikipedia

The skipper could have a printed maritime chart, crammed with essential information, like this one.

Chart of the Lune Estuary: Courtesy of Imray, Laurie, Norie and Wilson Ltd

We immediately see the difficulties of navigation and the narrowness of the Lune channel. However, the helpful map shows the locations of dangerous sandbanks, shipwrecks, various buoys, and the Plover Scar lighthouse. Important contacts are listed.

So, providing there are no typhoons, tsunamis, or hungry sea monsters, sailing up to Sunderland Point should be a piece of cake.

Not so three hundred years ago.

Navigation in 1737

Imagine we are aboard a ship bound for Lancaster, on the return journey from the West Indies with a cargo of raw sugar and coffee beans. The vessel may have paused in Ireland for fresh supplies, but now it is approaching Morecambe Bay.

The captain is at the helm. He is an experienced mariner, but uncertain about the entrance to the Lune.

He has a large but rudimentary set of equipment, which he uses expertly; the lives of a large crew depend on it. He has a compass, a sextant, a spyglass (telescope), a knotted rope to measure speed, a lead-weighted rope to measure depth, an unreliable clock, and sea charts.

He has no weather forecast, but with experience, he understands the significance of cloud formations and wind direction, which will alert him to weather changes. He sees a potential storm on the western horizon and must find safe anchorage.

There is no tide table. He must study the moon for a local assessment.

A pause for understanding.

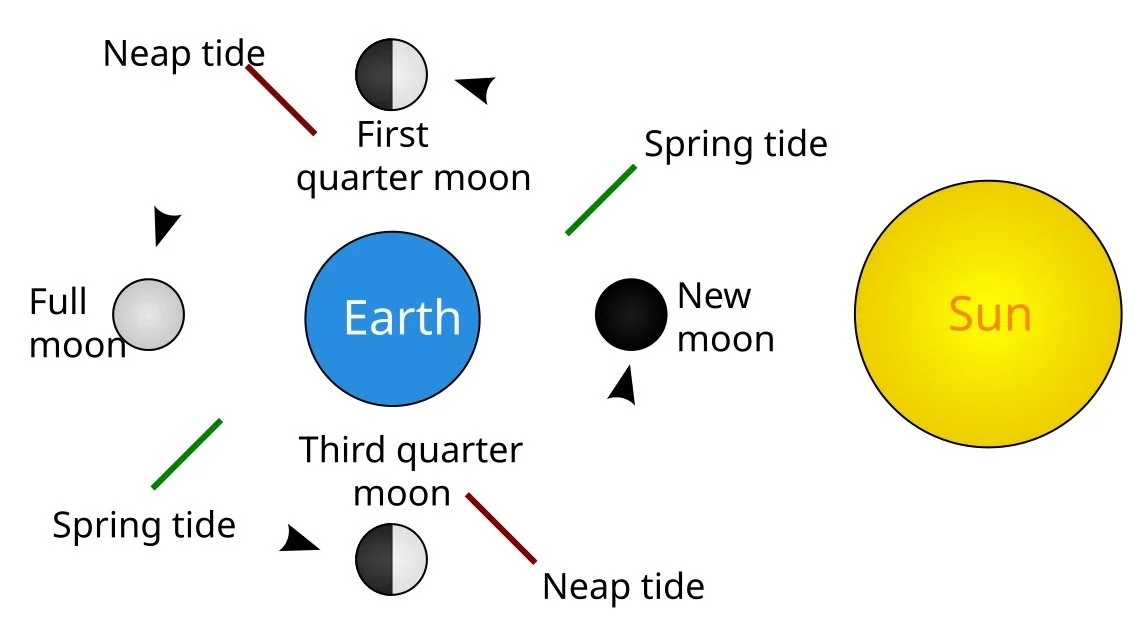

As we know, the moon governs the tides. Every day, the time changes, with two high tides approximately 12 hours apart, following a strict pattern over the roughly 4-week lunar cycle. Very simply, the higher, high tides – the spring tides – occur around the time of the full and the new moon. The lower high tides – the neap tides - occur in between. (see Paul’s detailed description)

This diagram shows the monthly lunar cycle.

The phases of the moon: source Wikipedia

The captain will have learnt ‘off by heart’ to read the waxing and waning phases of the moon; the timing gives a basic tide table. He knows it will be impossible to go up the Lune at any other time than a rising tide (and with favourable winds).

Approaching land, the hills of the Lake District have become visible, and with his spyglass, he thinks he can see Piel Castle (near Barrow).

The captain goes below deck to study his chart and instructions.

The Sea Chart

Sea charts were a matter of life and death: poorly drawn coastlines, missing sandbanks, rocks and shoals, or inaccurate depths led to shipwrecks.

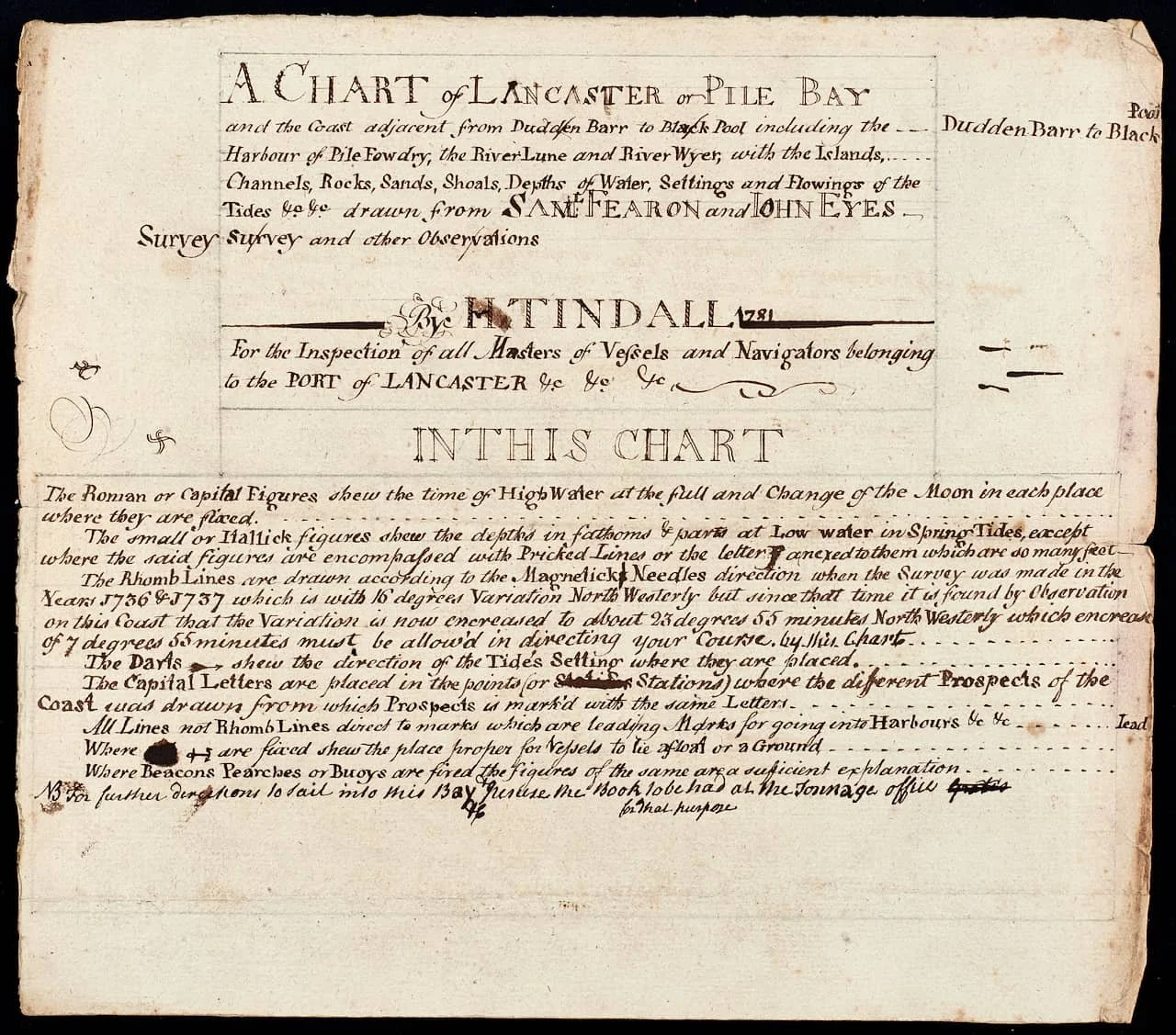

He is fortunate. On the table is a new chart just published in Liverpool by John Eyes and Sam Fearon, surveyed by H Tindall, covering Morecambe Bay. He also has the book of guidance that complements the map.

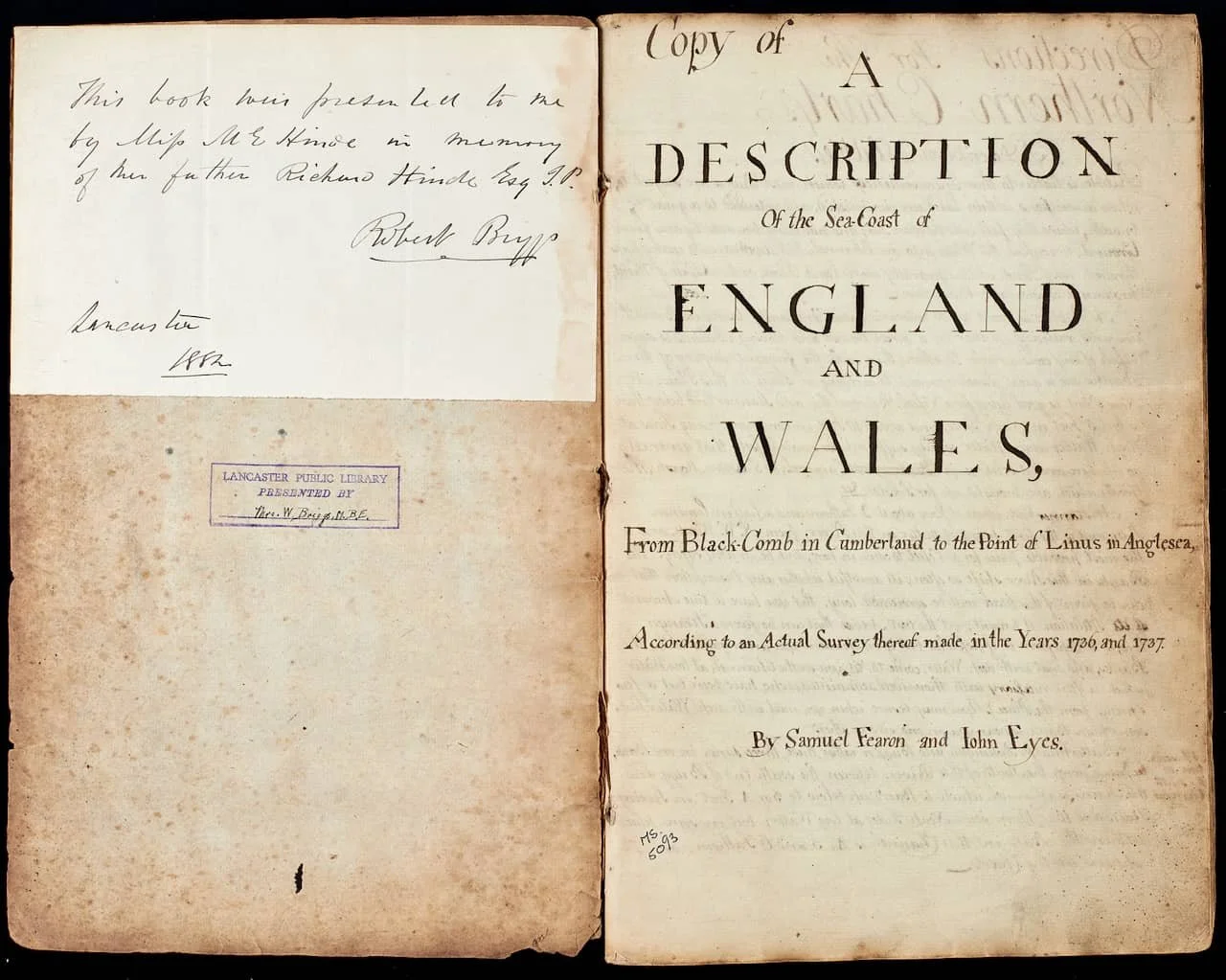

This is the introduction to a later version (1781) of that chart.

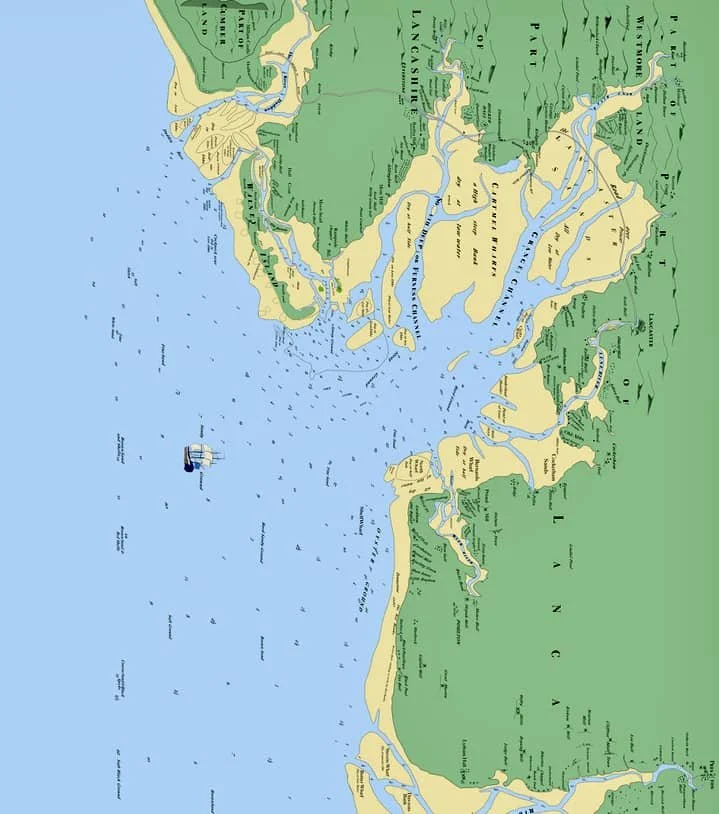

Eyes and Fearon chart: Courtesy Lancashire Archives.

This provides detailed instructions on how to read the chart and interpret the various symbols, lines and numerals.

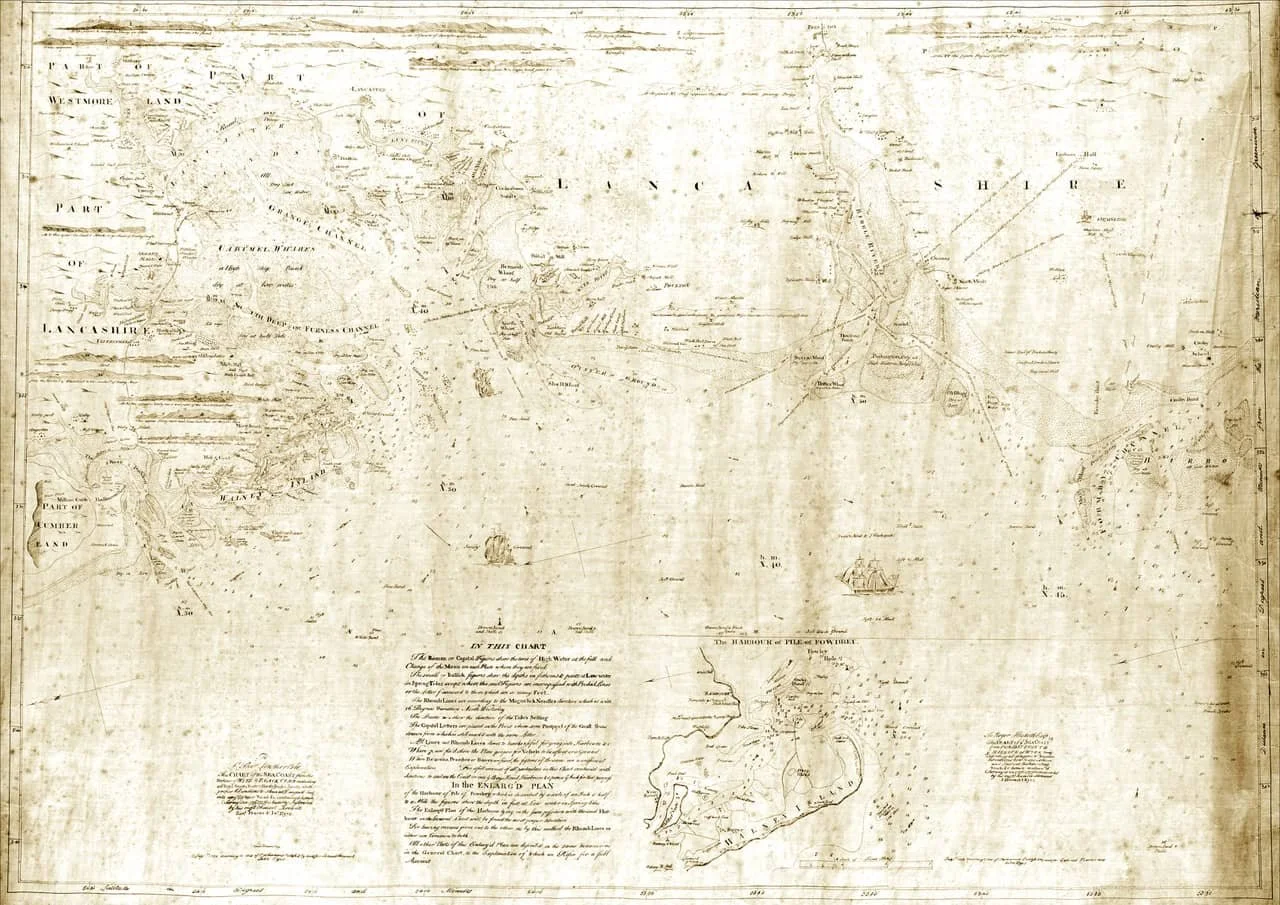

Here is the chart

Eyes and Fearon chart: Courtesy Lancashire Archives.

Unfortunately, the ageing of the chart makes it difficult for us to read. To give some idea of what it looked like. Paul Hatton has painstakingly recreated the chart.

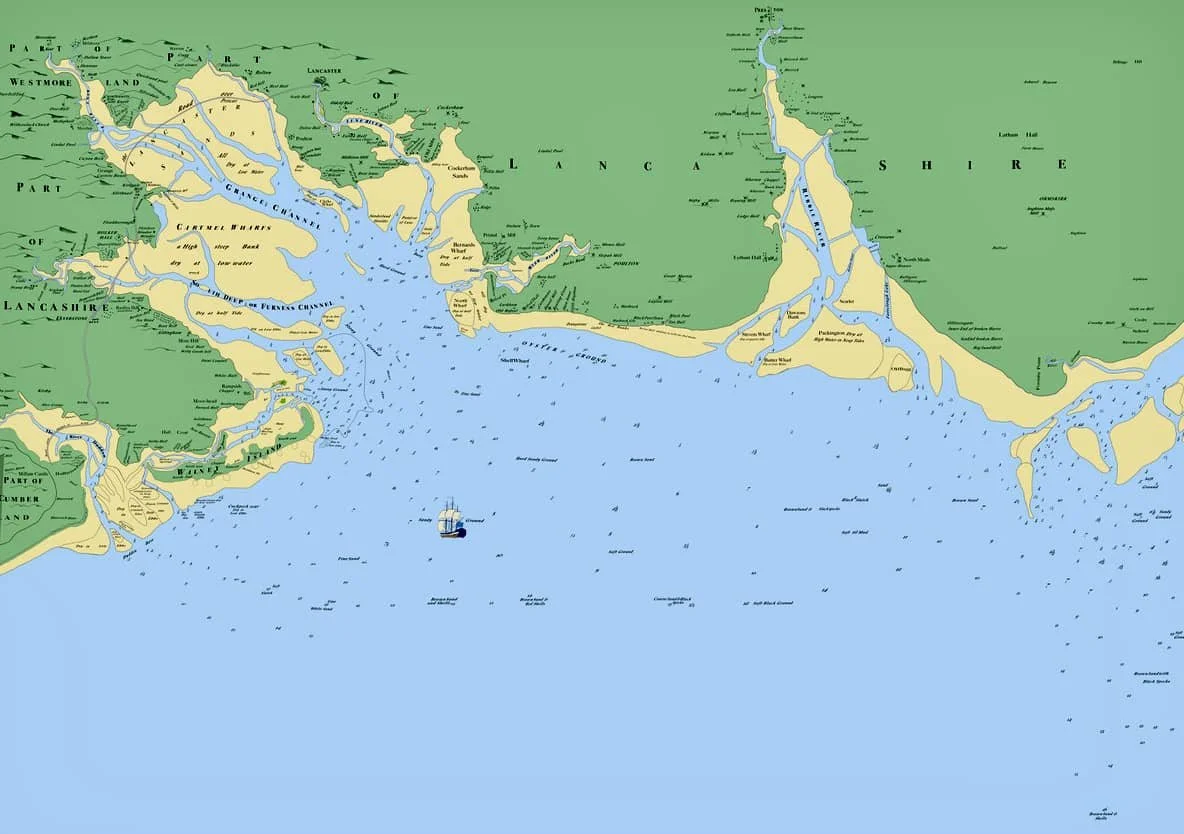

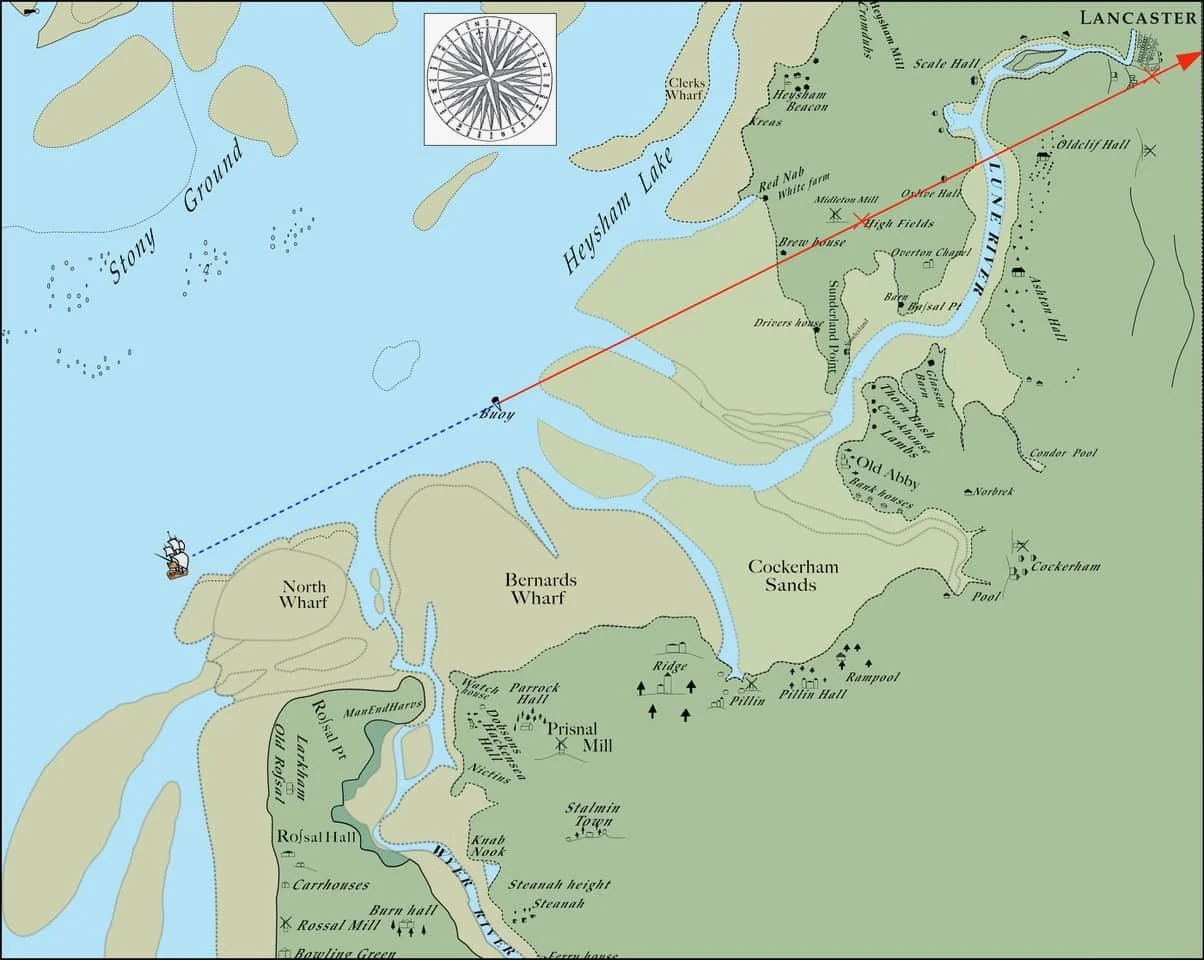

Eyes and Fearon chart recreated by Paul Hatton.

The chart is still confusing because it’s presented in a west-to-east format and not the traditional north-to-south, but this is how the captain sees the coast as he approaches.

This is vitally important - he needs visual directions to lead the ship to safe anchorage.

If we quarter-turn the chart, the shape of the Lancashire coast is now familiar.

Eyes and Fearon map with quarter turn: Paul Hatton

The voyage to safety

The captain, knowing there is a safe anchorage on the landward side of the Sunderland peninsula, reaches for the book of instructions (dated 1737).

The inside cover and page one of the Eyes and Fearon booklet: Courtesy Lancashire Archives.

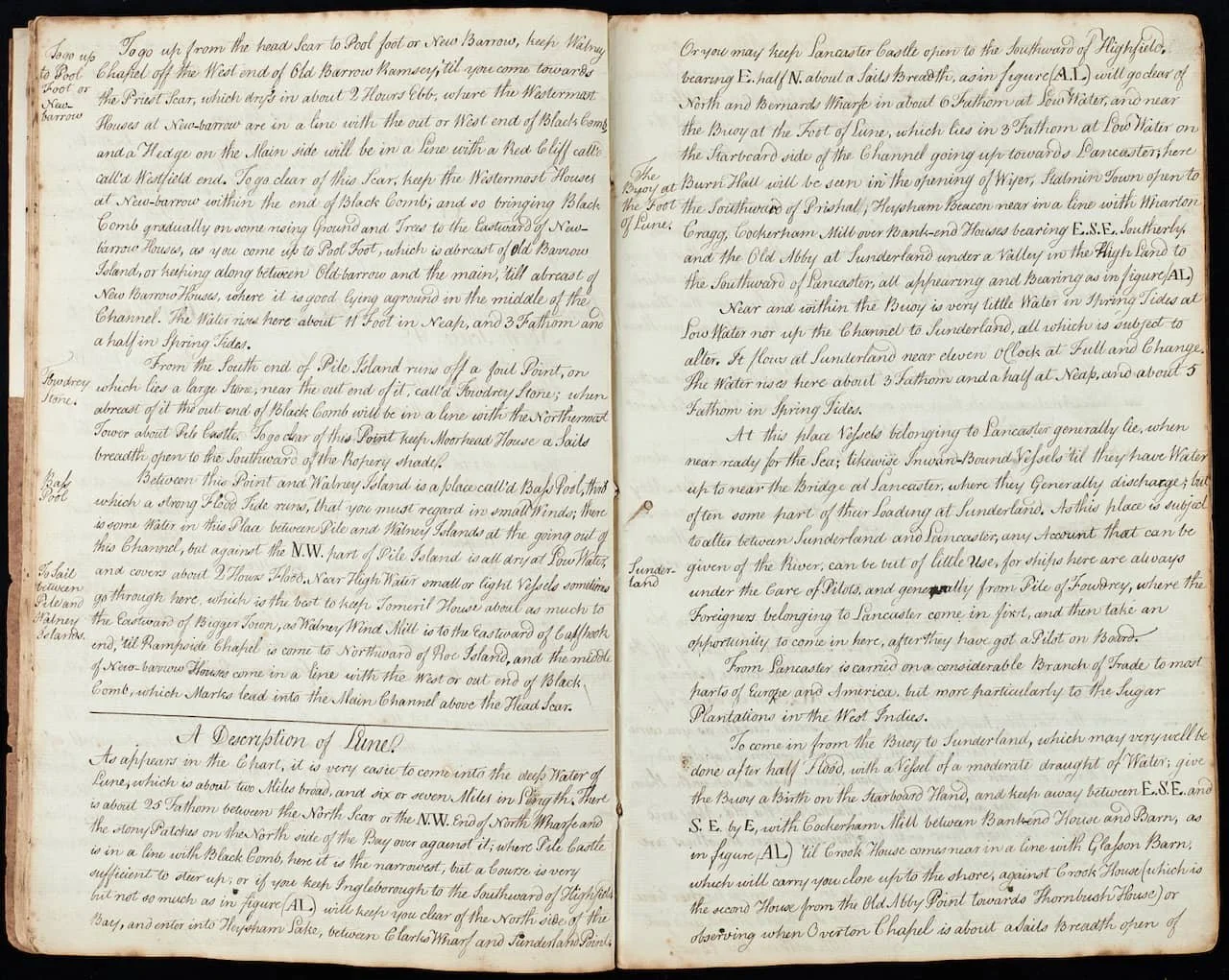

He leafs through the pages until he finds the River Lune, three-quarters down the left page.

Eyes and Fearon booklet: Courtesy Lancashire Archives.

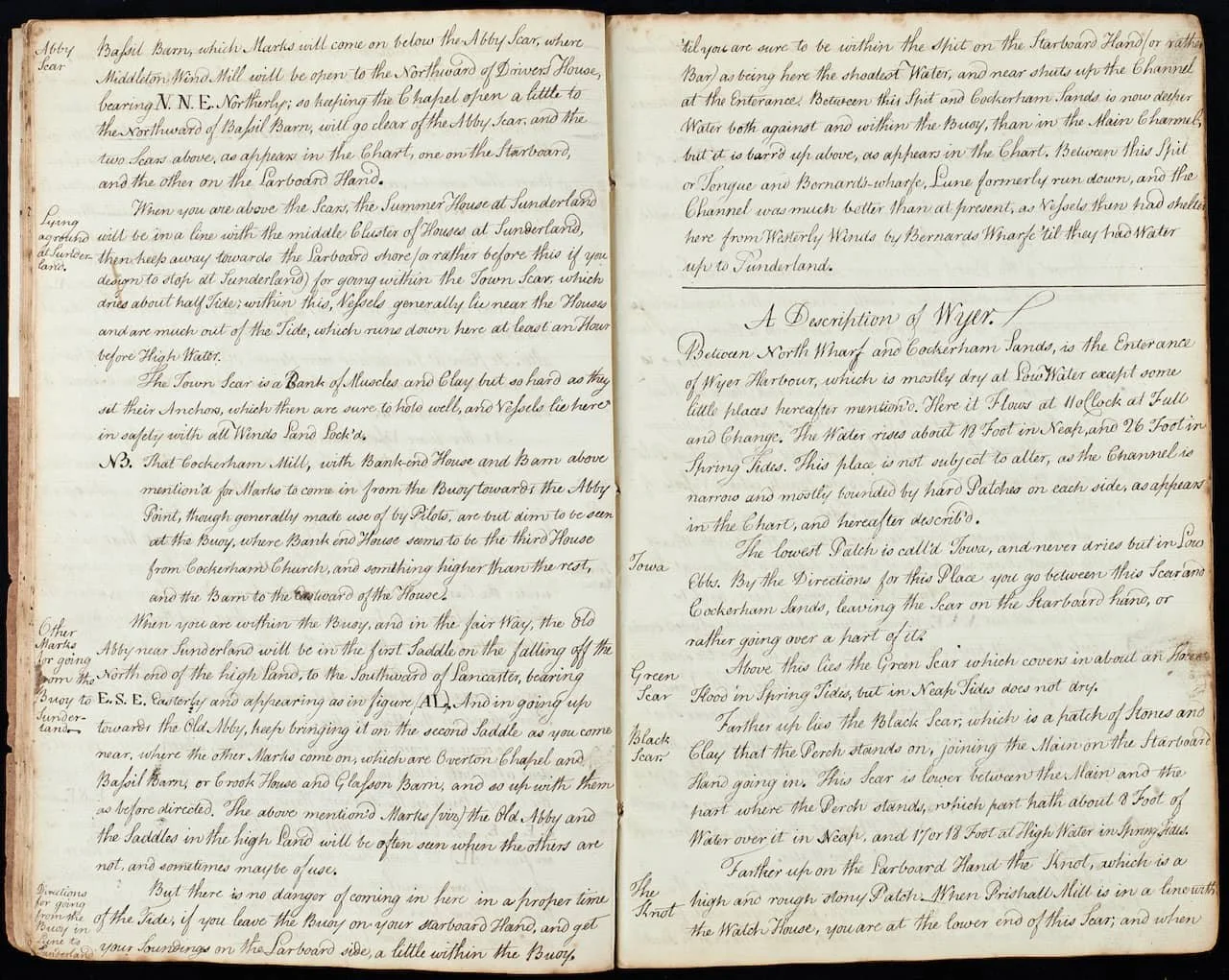

Then, turning the page.

Eyes and Fearon booklet: Courtesy Lancashire Archives.

He reads that the final stage to Lancaster requires a pilot, but he must navigate up the channel to Sunderland Point. He reaches for a large magnifying glass to examine the details of the entry into the Lune (west to east).

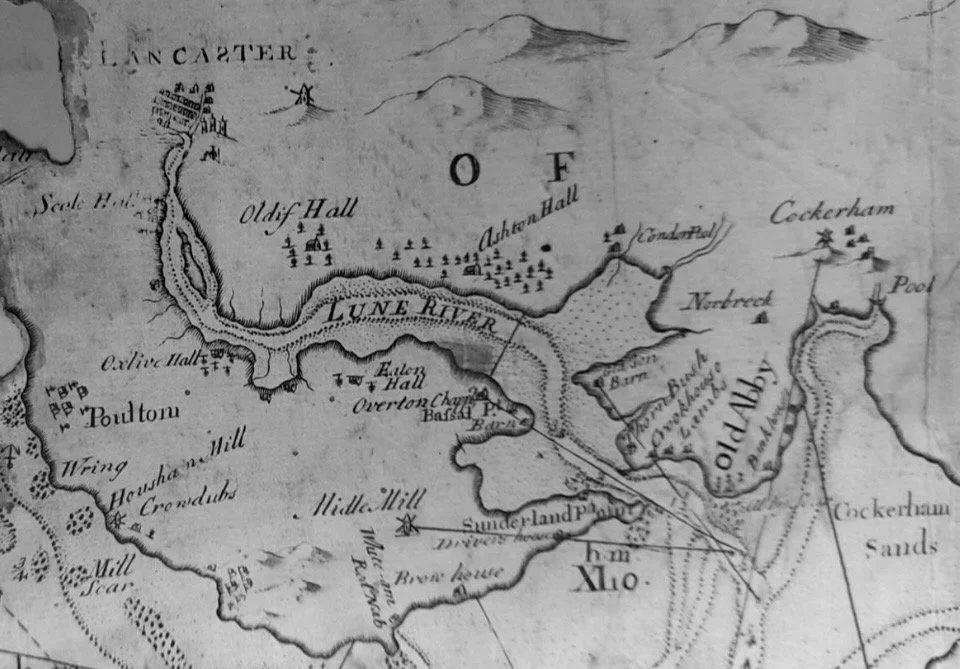

Extract from the Eyes and Fearon Chart: Courtesy Lancaster City Museums

Lines of sight

On the chart, we see strange straight lines. These are lines of sight. This means that when two features in the landscape, such as a church tower, a castle, or even a large barn, are aligned, the ship is in the correct position.

The captain fills his pipe with tobacco and grunts, looking again at the guidance notes.

This is what he reads….

The directions up to Sunderland Point

The language of three hundred years ago is difficult to understand; we have translated it into modern idiom, in bold, being careful to stay faithful to the original text, with our explanatory comments in italics.

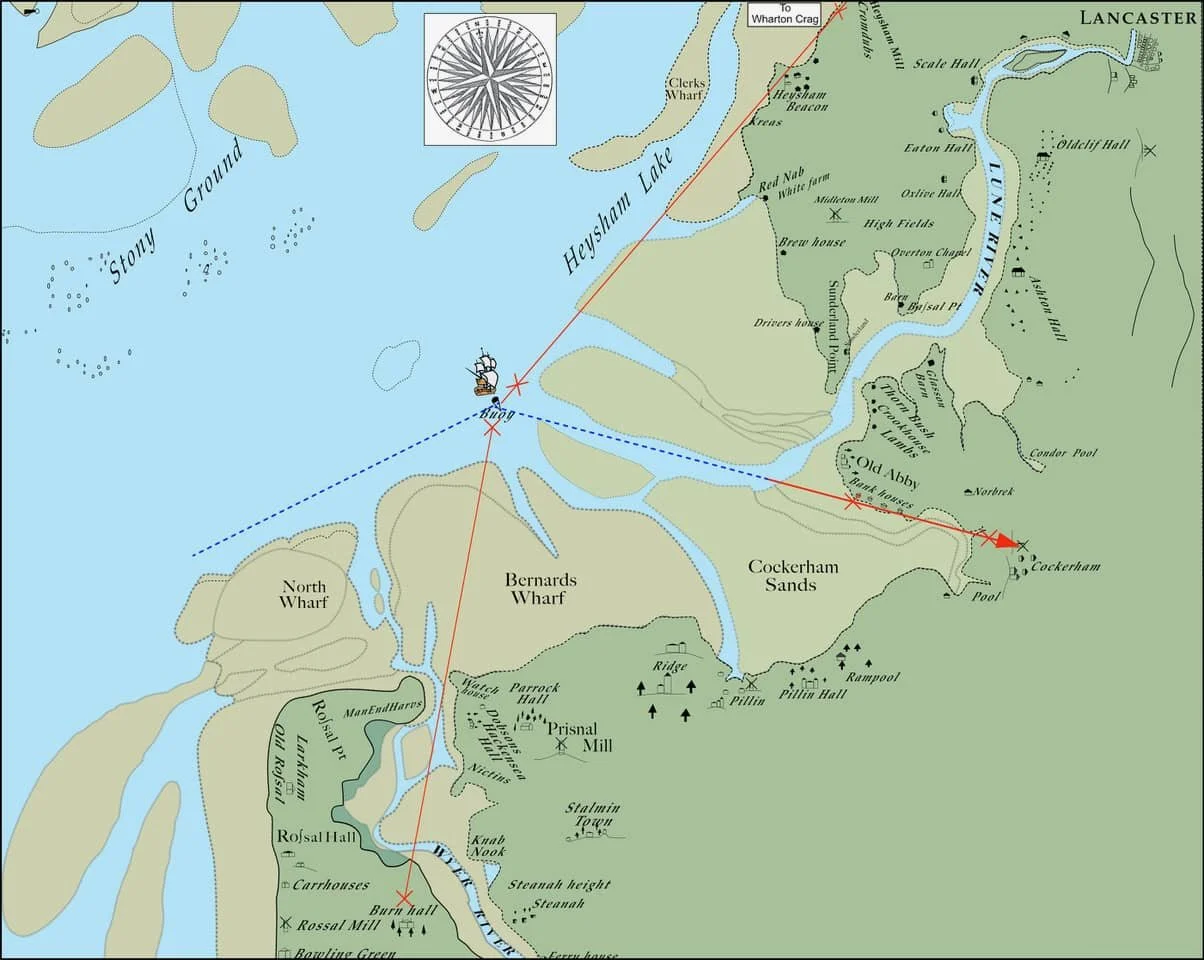

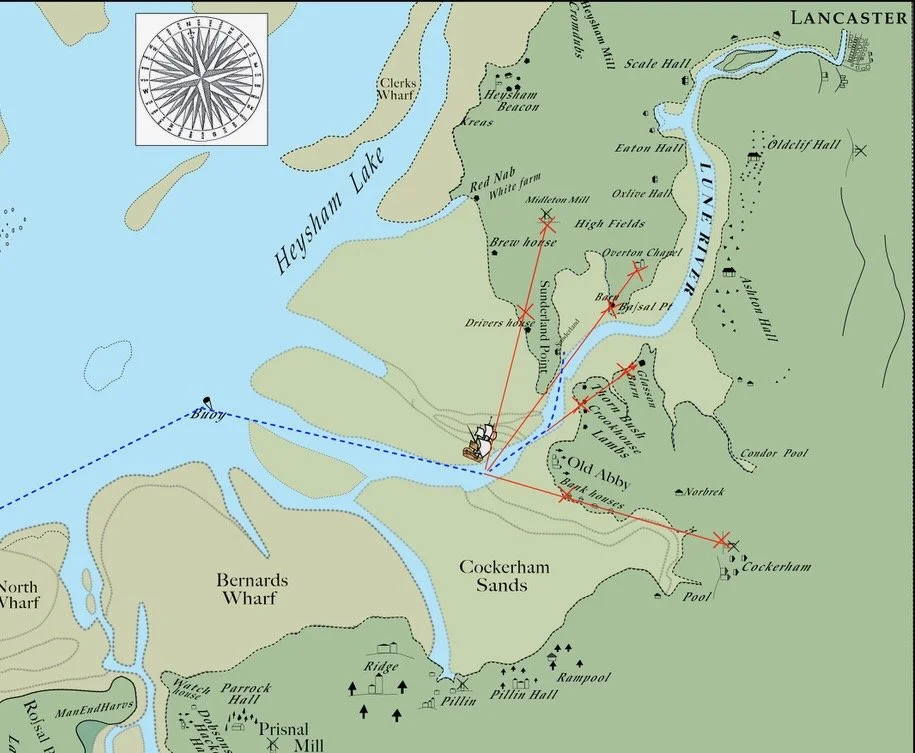

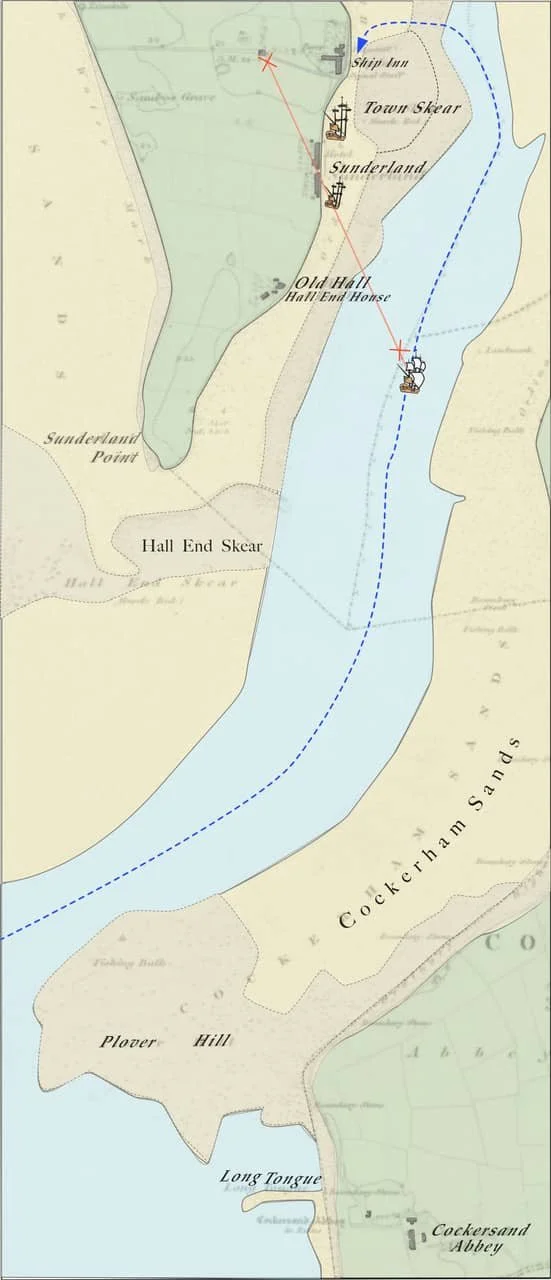

Paul has created special charts that illustrate these directions: the first three are based on the original map, and the last chart is based on the 1840s OS map.

Step One

Getting to the Buoy at the mouth of the Lune estuary

Reaching the deep waters off the Lune is straightforward. It measures two miles across and extends about six or seven miles along and is situated between the Stony Ground to the north and the sand bank known as North Wharf to the south. The depth there is 25 fathoms (150 feet).

Where Piel Castle (near Barrow) is in line with Black Comb (a Lake District hill), the channel is narrowest, but an easy course to steer. You will enter into Heysham Lake with Clarks Wharf (sand bank) to the northeast and Sunderland Point to the northwest.

Alternatively, if you keep a sight of Lancaster Castle to the south of Highfield (hills) on a bearing east-north-east plus a Sails breadth (a smidgen!), you will go clear of North Wharf and Bernards Wharf (sandbanks) with 6 fathoms (36 feet) of depth at low water.

You will then reach the buoy on the left side of the channel, which goes up to Lancaster.

In the early 1720s, the merchants of Lancaster, understanding the dangers of the Lune estuary, subscribed together to finance the first buoy – the Lawson family at SP contributed £5, as did Robert Lawson of Lancaster.

Our ship is in the deeper waters of Heysham Lake, keeping well clear of the stony ground to the north and close to the mudflats. He sees the Castle at Lancaster and the higher land over the Sunderland peninsula. By following this line of sight, he will reach the all-important Lune estuary buoy.

Note: There is very little water at low tide during the spring tides (the higher tides), at the buoy, or in the channel up to Sunderland. The channel is also subject to significant changes due to the river’s flow.

Regarding tide times, the high tide can be timed at Sunderland around 11 o’clock, near the time of the full and change.

The ‘full and change’ refers to the full moon and the new moon when spring tides – the highest tides – occur. The captain will have a printed book of the ports along the coast, which provides these timings. At Sunderland, it is at 11 o’clock, slightly earlier than it is today. By knowing the phase of the moon, he will be able to estimate the time of the next high tide accurately.

At the buoy, the tide rises three and a half fathoms (21 feet) on neap tides and five fathoms (30 feet) on spring tides.

This is key information: this gives the depths expected over the range of high tides

Notes

At this location (the buoy), vessels wait for favourable weather and the right moment on a rising tide to ensure sufficient water to reach the bridge at Lancaster.

Any account of navigation between Sunderland and Lancaster is of little use due to the changes in the channel. Ships from here are always under the care of pilots. Ships may also unload part of their cargo at Sunderland to allow for easier navigation in the lower depths of water towards Lancaster.

For ships of foreign origin, they would be expected to pick up a pilot from the Pile of Fowdrey (near Barrow).

From Lancaster, a considerable branch of trade is carried on to most parts of Europe and America, but more particularly to the Sugar Plantations in the West Indies.

Step Two

To be correctly positioned for the next stage of the voyage, perform the following visual checks: Burn Hall will be visible at the entrance of the River Wyre. Stalmin town lies south of Preesall. Heysham Beacon is roughly in line with Warton Cragg. Cockerham Mill will be situated above Bank-end Houses, towards the southeast, and the old Abbey (Cockerham), near Sunderland, lies under a valley within the higher land south of Lancaster.

Wait until half flood (between the time of low water and high water)

With the buoy on the starboard (right) side. Take an easterly direction, keeping a sight line of Cockerham Mill between Bank-end and Barn. Sail on until Crook House comes into sight line with Glasson Barn.

Our vessel is at the buoy. He takes in the lines of sight and takes a bearing to the southeast – keep going towards the old Abbey until Crook house comes into line with Glasson Barn.

This will bring the vessel close to the shore by Crook House, which is the second house from the Old Abbey Point towards Thornbush House.

To check this, a sight line to Overton Church should be a sail’s breadth (smidgen) away from Bazil Barn.

Step Three

You will have arrived at Abbey Skear.

Middleton (Village) will be visible in a sight line to the north of the Drivers’ House (on the west shore of SP). Now take a bearing to the Northeast, keeping Overton Chapel a little to the North of Bazil Barn.

Following this bearing, you will go clear of the Abbey Skear and the two skears that are shown on the chart – one on the Starboard side (right), the other on the Port side (left)

When in the correct position using lines of sight, the vessel can change bearing to northeast up the channel towards SP

When past these skears, the Summer House at Sunderland will be in a sight line with the middle cluster of houses at Sunderland (Second Terrace), keep to the Starboard side where the channel runs deepest.

Our vessel has passed the skears by the Point End and the Old Abbey and is given a sight line to keep right where the channel is and to avoid Town Skear, which is thought to have been a much greater hazard in the early 1700s, than today.

However, if you plan to stop at Sunderland, go within the Town Skear – which surfaces above the water at mid-tide - and the shore. Vessels generally lie near the houses and are much out of the tide. The shore is free of any tide at least an hour before high water.

“The Town Scar is a Bank of Muscles and Clay, but so hard as they set their Anchors, which then are sure to hold well, and Vessels lie here in safety with all Winds Land Lock'd “(Extract of original text).

The writer then lists essential notes to consider when reading the chart and instructions – we reproduce them all.

NB

Cockerham Mill, Bank-end House, and Barn, widely used by pilots as sight marks to assist navigation from the buoy to Abbey Skear, are often only faintly visible from the buoy. Remember that Bank-end House is the third from Cockerham Church and is taller than the others, and the Barn is situated to the west of the House.

When you are at the buoy, and in the correct position, the Old Abbey near Sunderland will be in the first saddle of land, falling away from the north end of the higher land. It is to the south of Lancaster on a south-easterly bearing.

As you go towards the Old Abbey, keep it in line on the second saddle of land, until you reach the next set of sight marks, which are Overton Chapel with Bazil Barn, Crook House and Glasson Barn. Proceed as in the earlier instructions.

The Old Abbey and Saddles in the higher land are often seen when others are not, so they may sometimes be of use.

There should be no danger coming from the buoy to Sunderland, provided you have correctly timed the tide, the buoy is on your starboard (right) side, and you have taken depth soundings on the starboard side, a little away from the buoy.

Very important: keep to the starboard side of the buoy and stay clear of the mudbanks on the right, as this is the shallowest water and it blocks the entrance to the channel. Here is the remnant of the old channel where deep water remains, but it is blocked further up the estuary.

This old channel of the Lune was much better than the present one, as it allowed vessels to shelter by Bernards Wharf and Cockerham sands until there was enough tide to proceed up to Sunderland.

Anchored

The ship has dropped anchor, and the tide continues to rise, small boats will be rowed out to unload cargo. Waiting on the shore will be the ‘tide waiter’ (customs officer), coming to check the goods for taxation.

Most times, this will be done quickly, and with a pilot on board, he slips anchor and continues the journey to Lancaster. Sometimes there may be a wait for the next high tide; if so, perhaps an evening of sea songs and some light refreshments at the Ship Inn….

We are greatly indebted to Paul Hatton for his knowledge of sailing and the many hours spent recreating the original chart and additional charts.